Letters From Andy

Ladybug Letters

Take a “Psych-idyllic” trip and come visit us.

Hi Friends: Sharing our farm with visitors is a rewarding experience. A few years ago Starr & I extended a formal invitation to any passing Bluebirds to please come and hang out on the farm. Much thanks to our friend, Jo Ann Baumgartner, for her help and advice on getting and placing the bird houses. This year a Bluebird couple took us up on our invitation and moved in. Bluebirds are great creatures to have on a farm like ours that grows its produce without recourse to insecticides since they eat lots of insects that could damage our crops. It was disturbing to know that Bluebird populations have crashed across the US as their habitat has gotten destroyed. It feels good to try and push back against this trend by creating a welcoming habitat. We want to grow healthy, tasty herbs, greens, fruits and flowers for you, but in a way that honors and protects the diversity and beauty of the natural world.

You all are invited to visit the farm too, though we will steer clear of the Bluebirds’ house and give them their privacy. We still have a couple of open spots for this upcoming Saturday June 21st Summer Solstice Self-Care event from 11-2 pm. Tickets are on our website at Mariquita.com . The gate opens at 10:30. This event promises a taste of a variety of self-care offerings while celebrating the Summer Solstice with us. We will be joined by several event guides and practitioners that will provide you with a taste of their art and profession such as a mini facial massage, an acupuncture session, a sound bowl meditation and walk in the very purple lavender labyrinth or a sit down with a channeler. All of this and a nice time to enjoy the gardens and hear the birds.

We’ve also been opening the farm for a series of lavender U-Pick events. Check the website for signup details.

Besides our public events we do open the farm and host events for groups and individuals; painting clubs, blessing ways, staff parties, and fund-raising dinners and picnics have all been on the calendar. Let us know if you have an event in mind that would benefit from a beautiful, peaceful rural surroundings with an out-door kitchen, a handy labyrinth and a lot of flowers! Starr does flowers for events and weddings too. Let us know.Given that some of you may drop in I thought it would be fun to share some photos of the various creatures that have passed through or taken up residence here at Mariquita Farm. Thanks for checking in. Andy & Starr:

This little frog has found a beautiful little studio apartment on the farm. In the 1920s my Great Grandfather leased the property to a flower grower who planted Calla lilies. That grower is long gone but some Callas persist in the swampy area beyond the edge of the field.

This cute little fox let me photograph it as it made its evening walk through our spiral garden. Foxes like to eat gophers and ground squirrels so I like it when they visit. Sometimes we hear them yipping and barking in the night time. They pose no threat to people.

I found this little Robin’s egg on the pathway to the windmill field. I’m not sure how it got there but lots of wild critters want to eat bird eggs so I’m sure there was some drama.

Every magic garden needs at least one snake! This is a mature gopher snake that has made its home on the farm. Gopher snakes are a farmer’s best friend.

This is a baby gopher snake, not much longer than a pencil. May it grow up to be big and fat!

The lavender field is breaking into bloom as I write. I wish I could photograph the scent! Besides the honey bees that come from the hives on the farm the lavender patch also host numerous bumble bees and othe native bees. This flower patch literally hums. But don’t worry; the bees are all hard at work and they don’t feel threatened by us or pose a threat. Just walk down the pathway mindfully, pay attention that you don’t grab a bee when you’re picking lavender, and everybody will bee happy.

Starr uses her farm store as a herb drying room when it’s not open to visitors. One hundred years ago this little building was a carriage house turned garage that housed my Great Grandfather’s Pierce Arrow motor car. But today it smells like lavender.

This silly turkey was one of the first visitors to the farm store after Starr created the space to show off the herbs, flowers, and other goodies form the earth that she sell, but the turkey was only interested in the “other” turkey!

Yep, we have Mountain lion visitors to the farm. This beauty was photographed just beyond the deer fence that encircles the gardens. Farmers know that Mountain lions are the best “deer fence.” Mountain lions are no pussy cats, that’s for sure, but they were here first and deserve our respect. I’m happy that we almost never see them, but I’m glad that they’re there. It’s impossible to farm where there are too many deer.

Before they were “The Beatles! ” they were a cover band called “the Silver Beetles.” So I smile when I see these iridescent, metallic beetles on the farm. Yeah, yeah, yeah! Nature is so psychedelic. Starr and I want our farm to be “Psych-idyllic!”

And I’m glad that house cats are the size they are. This kitty’s name is Tassajara, or “Tassa” for short, and she follows me around like a dog and finds delight and interest everywhere she goes. What a way to live!

.

|

Hi from Mariquita Farm

Our 2025 season’s first lavender harvest; Ellagance Purple Lavender. Other varieties of lavender will come into bloom as the season progresses.

Hi Friends: We at Mariquita Farm didn’t go anywhere, but we’re back, and we’ve been busy in our “off-season.” The potato crop is in the ground and the first vines are breaking the soil surface to find the sun. Our Otto File polenta corn stalks are already 6 inches tall, the tomatoes and peppers are being transplanted into their beds as I write, and more herbal, floral and vegetable crops are being sown in the greenhouse and fields. The roses are blooming, lavender is budding, bees are buzzing, and the citrus trees are heavy with fruit. We are growing the crops and creating the gardens for you. Here is a brief sketch of the events that we are planning for the year:

World Labyrinth Day:

Join us for a guided walk in our eleven circuit Labyrinthine path through hedges of English, Spanish and French lavender. We’re celebrating World Labyrinth Day, where people around the globe will be participating in a walking meditation for World Peace that rolls through the time zones- “Walk as One at 1”. Sunny or cloudy, the day will be beautiful and the flower power of the thousands of lavender plants will be strong!

Our Day includes a walk with farm owners Starr Linden & Andy Griffin through the flower gardens that embrace the Lavender Labyrinth where we will stop to smell the roses. They’ve planted 200 Rose Bushes over the last three years, and some of them will be in full bloom. Learn about the different kinds of roses that exist, from the ancient China roses to the highly scented European heirlooms like the Gallica, Bourbon, and Damascus roses. We have modern Hybrid Tea roses planted out, and hardy Rugosa roses, Wild roses, climbers, miniatures, and even the sprawling heirlooms that are climbing tall pines.

I just finished getting our crop of Otto File polenta corn into the ground when I took this picture. Otto File is an heirloom Italian corn variety appreciated for the high quality cornmeal it can produce. We also grow Oaxacan Green corn and a lovely red dent corn.

Summer Solstice Self Care Day:

Join us at Mariquita Farm where you can relax and enjoy the countryside. You can explore the gardens filled with flowers, while looking out at hillsides covered in citrus and roses. Indulge yourself in a variety of self-care offerings while celebrating the Summer solstice with us! We will be joined by several event guides and practitioners that will provide you with a taste of their art and profession.

Offerings include:

- Facial Massage Session

- Acupuncture Points for Stress

- 15 Minute Channeling Session

- Labyrinth Walk

- Sound Bowl Meditation

Can you find the cat in this photo? It was a warm day and she found respite from the sun by snoozing in the shade of the fava beans.

We grow over 200 roses for fun, for the petals which we sell fresh or dried, and for the bees. This is “Mr. Lincoln,” about to bloom.

Lavender U-Picks/ Herb U-Picks TBA: Follow the website and this newsletter for updates. We’ve got many varieties of basil and other herbs in the ground and we will be offering U-Pick opportunities for cooks & crafters.

Pop – Up Sales with our tomatoes, flowers, fruits, herbs, and other vegetables. TBA as the harvests allow.

Besides our public events we do open the farm and host events for groups and individuals; painting clubs, blessing ways, staff parties, and fund-raising dinners and picnics have all been on the calendar. Let us know if you have an event in mind that would benefit from a beautiful, peaceful rural surroundings with an out-door kitchen, a handy labyrinth and a lot of flowers! Starr does flowers for events and weddings too. Let us know.

Starr coming down the drive with a cart full of flowers for our friends at GatherFloraLA the LA Flower Market. We ship to LA weekly and serve local folks too.

A recent drone shot of the labyrinth.

I took a walk in the forest with the cat, Samson.

.

|

A Ladybug’s Secret Garden

When several recent visitors, at different times and completely unprompted, used identical language to tell Starr & I that our farm was “magical,” it got us thinking; “Why?”

I’m a farmer, not a magician, so I stand ready to be corrected by any Magus who might read these notes, but it seems to me that magic is always extraordinary, never “business as ordinary.” Farming, by contrast, is precisely a business. Nor is magic transparent, the way a legitimate business ought to be, or even easily explainable to investors, regulators or tax collectors. If we are to believe the AI bots lurking under the internet bridge, farming contributed roughly $1.537 trillion to the $ US GDP in 2023. What did magic do for capitalism? Who could know? Magic is mysterious. Besides, is everything of value measurable in dollars, pounds, pesos yen or bitcoin?

Magic is “occult.” The word “occult” may sound evil or threatening to some Christian Fundamentalists’ ears, but it’s just Latin for “hidden” or “secret.” Think about it; the magic on display in the public square is the pulling of bunnies from hats. Doesn’t the deeper magic always happen in sacred groves, away from the gaze of the uninitiated rabble, where the sorcerers and witches gather in a circle for their ceremonies, illuminated only by moonlight or by the coals glowing from under the cauldron? Unless you are raising rabbits for meat or fur, the last thing any farm needs is another bunny. So what are the things that could make Mariquita Farm “magical?”

When my daughter was a girl she played in the redwood grove too. My Grandparents got married in these redwoods. It’s a sacred grove.

For one thing, our farm is at the end of a private road and you have to go through three gates to enter the property. (Mystical numerologists will tell you that 3 is a magic number, a perfect number, and the number for harmony, wisdom, and understanding.) Even locals who grew up in our Corralitos/Salsipuedes

Magical thinking does seem to look back in time to a more mysterious era. The newest AI meme fodder available for public consumption on Insta or Tik Tok can never be as magical as something inscrutable from the deep past. In the canyon below our herb field there are redwood trees, including one broken giant that must be 1000 years old. Maybe the proximity of such a wise and ancient life form casts a spell over our herb field.

Plants play an important role in magic; they are not mere commodities like cotton or alfalfa or head lettuce. When I was a child in the 60s and this property was my grandparent’s sheep farm I would visit the redwood groves and bathe in their magic. Then I’d come to the house and my grandma would scrub the poison oak off. When my uncle was a child in the 20s and this property was his grandparents’ place, he played in the redwood groves. When my uncle sold me the ranch in 1998 he put a deed restriction on the property such that the redwoods could never be cut down. I signed the documents happily; this land belongs to the redwoods and the creatures they tower over- we’re just passing through.

Redwoods are majestic, but all plants are magical in some way. Anyone who has ever watched a seed germinate can feel the mystery if they let themselves. Starr and I have planted lots of flowers, so the landscape is splashed with color. All the roses and snapdragons blooming may seem magical enough but as you walk around the property you will see — and smell—- a lot more than pretty colors. Magic engages all the senses and incense is a core magical tool to connect with arcane realities. By coincidence and design we grow a lot of powerful, aromatic plants on the farm that have healing powers, from various basils, mints, sages and lavenders to more arcane plants like huacatay, cempasuchil, and hoja santa. And of course we plant the holy trinity of corn, squash and beans. (There’s your magical number 3 again.)

The labyrinth is modeled on the floor plan of the Medieval labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral.

Symbols count for something. We chose to plant our lavender patch in the form of a gigantic labyrinth 110 feet in diameter. Then Starr fit a cool little stone spiral walk into an unoccupied nook of the yard and we were pleased to see it sprinkled with volunteer wild violas in the spring. The fact that we didn’t even plant the Johnny Jump Ups seemed magical to us. If you look carefully under the roses or behind the cacti you will see a growing population of Gnomes who remind us of the mysterious forces at wor k and play undergroundSo maybe our farm is magical. We hope so, and we invite you to come see for yourself; here is a brief outline of a number of events we have coming up soon:

Ziggy The Gnome stands sentinel under the roses and cacti.

Outstanding in the Field, is bringing their traveling celebration to the farm on May 31st. Mariquita Farm was the site of the very first Outstanding in the Field dinner twenty five years ago and we are excited to come full circle after a quarter of a century with a 25th anniversary meal prepared by Chef Gus Trejo from The Dream Inn’s Jack O’Neil restaurant using produce from our farm and from our friends and neighbors at Lonely Mountain Farm. The wine pairings will be from John Locke/Birichino. It’s going to be tasty and the lavender labyrinth will be in bloom, so it’s going to be an aromatic time too. Click here for link https://outstandinginthefield.com/

A silly wild turkey admiring its reflection in the door to Starr’s farm store, where she sells her shrines, dried herbs, crystals, and preserves.

2. We will host a series of Lavender U-Pick with a first date on Saturday, June 7th. We will keep the U-picks going through August 1st and perhaps longer. A car full of folks can come and pick 5 bundles. Get all the details and make your reservation at Mariquita.com under events. Other herbs, like basils, thymes, oreganos, etc will be available for U-pick at (dates tba, check newsletter updates)

3. Summer Solstice Self-Care on Saturday, June 21st will bring together a grand group of special practitioners for a three hour journey into self-care. You can relax and enjoy the countryside, explore the gardens filled with flowers, while looking out at hillsides covered in citrus and roses. Indulge yourself in a variety of self-care offerings while celebrating the Summer solstice with us! We will be joined by several event guides and practitioners that will provide you with a taste of their art and profession. https://www.

.

Besides our public events we do open the farm and host events for groups and individuals; painting clubs, Blessing Ways, staff parties, baby showers, and fund-raising dinners and picnics have all been on the calendar. Let us know if you have an event in mind that would benefit from a beautiful, peaceful rural surroundings with an out-door kitchen, a handy labyrinth and a lot of flowers! Starr does flowers for events and weddings too. Let us know.

|

.

|

Hi from Mariquita Farm

Our 2025 season’s first lavender harvest; Ellagance Purple Lavender. Other varieties of lavender will come into bloom as the season progresses.

Hi Friends: We at Mariquita Farm didn’t go anywhere, but we’re back, and we’ve been busy in our “off-season.” The potato crop is in the ground and the first vines are breaking the soil surface to find the sun. Our Otto File polenta corn stalks are already 6 inches tall, the tomatoes and peppers are being transplanted into their beds as I write, and more herbal, floral and vegetable crops are being sown in the greenhouse and fields. The roses are blooming, lavender is budding, bees are buzzing, and the citrus trees are heavy with fruit. We are growing the crops and creating the gardens for you. Here is a brief sketch of the events that we are planning for the year:

World Labyrinth Day:

Join us for a guided walk in our eleven circuit Labyrinthine path through hedges of English, Spanish and French lavender. We’re celebrating World Labyrinth Day, where people around the globe will be participating in a walking meditation for World Peace that rolls through the time zones- “Walk as One at 1”. Sunny or cloudy, the day will be beautiful and the flower power of the thousands of lavender plants will be strong!

Our Day includes a walk with farm owners Starr Linden & Andy Griffin through the flower gardens that embrace the Lavender Labyrinth where we will stop to smell the roses. They’ve planted 200 Rose Bushes over the last three years, and some of them will be in full bloom. Learn about the different kinds of roses that exist, from the ancient China roses to the highly scented European heirlooms like the Gallica, Bourbon, and Damascus roses. We have modern Hybrid Tea roses planted out, and hardy Rugosa roses, Wild roses, climbers, miniatures, and even the sprawling heirlooms that are climbing tall pines.

I just finished getting our crop of Otto File polenta corn into the ground when I took this picture. Otto File is an heirloom Italian corn variety appreciated for the high quality cornmeal it can produce. We also grow Oaxacan Green corn and a lovely red dent corn.

Summer Solstice Self Care Day:

Join us at Mariquita Farm where you can relax and enjoy the countryside. You can explore the gardens filled with flowers, while looking out at hillsides covered in citrus and roses. Indulge yourself in a variety of self-care offerings while celebrating the Summer solstice with us! We will be joined by several event guides and practitioners that will provide you with a taste of their art and profession.

Offerings include:

- Facial Massage Session

- Acupuncture Points for Stress

- 15 Minute Channeling Session

- Labyrinth Walk

- Sound Bowl Meditation

Can you find the cat in this photo? It was a warm day and she found respite from the sun by snoozing in the shade of the fava beans.

We grow over 200 roses for fun, for the petals which we sell fresh or dried, and for the bees. This is “Mr. Lincoln,” about to bloom.

Lavender U-Picks/ Herb U-Picks TBA: Follow the website and this newsletter for updates. We’ve got many varieties of basil and other herbs in the ground and we will be offering U-Pick opportunities for cooks & crafters.

Pop – Up Sales with our tomatoes, flowers, fruits, herbs, and other vegetables. TBA as the harvests allow.

Besides our public events we do open the farm and host events for groups and individuals; painting clubs, blessing ways, staff parties, and fund-raising dinners and picnics have all been on the calendar. Let us know if you have an event in mind that would benefit from a beautiful, peaceful rural surroundings with an out-door kitchen, a handy labyrinth and a lot of flowers! Starr does flowers for events and weddings too. Let us know.

Starr coming down the drive with a cart full of flowers for our friends at GatherFloraLA the LA Flower Market. We ship to LA weekly and serve local folks too.

A recent drone shot of the labyrinth.

I took a walk in the forest with the cat, Samson.

.

|

Happy Thanksgiving

Behind the palm trees are the orange trees. At this time the entire area was covered in orange groves for miles and miles. It smelled heavenly when the trees were in bloom and it stuck like hell when the farmers ignited the smudge pots and burned oil to keep the threat of frost at bay.

If you know where to look there are still tiny fragments of the past clinging on to the present in the Inland Empire- an old orange tree in a yard here and there, an building that was once a fruit packing shed etc. Mostly you can read about the past in the street signs, where citrus themes like “Valencia St.” or “Orange Show Speedway” point to the past.

Happy Thanksgiving and thank you for supporting our farm this year. Thanksgiving always marks the end of a season and a moment of rest before we commence a new year’s production schedule, so it’s a good time to look back and reflect. This year wasn’t the easiest of years, with a cold, wet, and late start for planting, and the cool weather continued, punctuated with heat spells that were hard on the tomato crop. But we made it through. That another year has passed by, and so quickly, has me thinking about time.

The horse in the top picture was named Fanny. The boy in the woman’s lap is Jack, Fran’s father. Fran is my mother in law.The woman holding Jack is her grandmother, Magdalena. They were posed in their orange orchard in Colton, California, at the corner of Olive and Rancho, in 1924. This last week, Fran, my mother in law, and I, drove out to Colton, a hundred years later, to revisit the scene. Thankfully, the palm tree is still there. Everything else in the neighborhood has changed dramatically for miles around. Millions and millions of people now live where the orange groves once carpeted the valley floor. “Time waits for no one,” I’ve heard. The traffic certainly wouldn’t wait for me either, so I wasn’t able to stand in the street to recapture the precise perspective of the old photo. I wanted to hug the old palm tree and hear it tell me a hundred years of stories.

I decided to go home and look through my own photographs to see how well my family has documented the changes on this little patch of ground we’ve called home for the last 120 years.

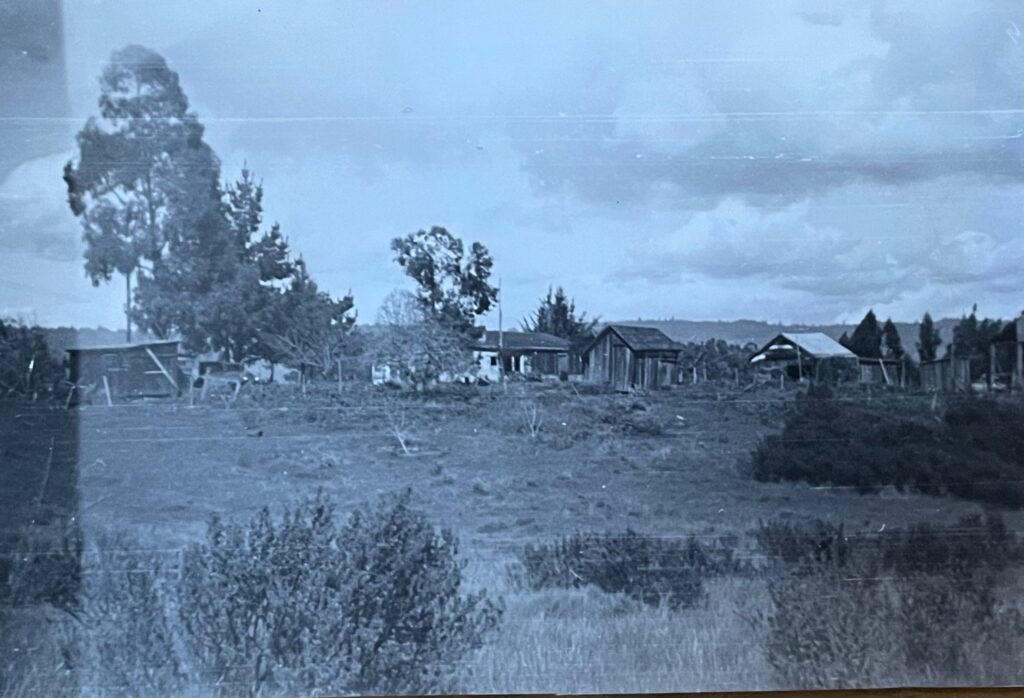

The picture below was taken sometime in the 1930s when the farm was being used to graze livestock. This field is where we have recently situated our lavender labyrinth. You can see that my family kept cattle at the time, not sheep as they did later on, because the coyote brush in the field would have been nibbled back by sheep, whereas the cows prefer to lick up grass. If I stopped farming the field tomorrow the coyote brush, Baccharis pilularis, would promptly pop up again. Time doesn’t wait but Baccharis has the patience and persistence to wait and wait and wait for its chance to return. Sometimes I get distressed when I see how aggressively stupid we humans are about fouling the natural world we’re born into, but then I remember that nature has all the time in the world to heal itself. I’m thankful that I’ve had the opportunity to farm this land that my great grandfather worked on 100 years ago and hopefully “do it right.”

Only the barn at far right of photo is still standing, albeit remodeled on the same footprint. The other outbuildings are now gone and our present day home is just off the left hand side of photo. My grandfather built it with the lumber he re-used from the old house that is in this photo. And the “old house” had been built using the wood from the “old, old house,” which had been built from the redwoods logged on the property in the 1860s.

Here’s the corner of the field on a quiet Sunday morning in 1987 when a hot air balloon landed after it ran out of gas overhead. The pilot gave us a bottle of champagne which he kept aboard for emergencies like this.

Our lavender labyrinth is now mature. This perennial lavender planting occupies the emotional center of the field and around the margins of the labyrinth we plant our other crops. During our 2025 growing season we intend to plant 18 beds of herbs, ranging from anis hyssop, thru a spectrum of basils to lemon thyme, marjoram, nepitella, oregano and zaatar. We rotate crops, so where the pumpkin patch grew this year we will plant our sacramental marigold patch next year. We look forward to inviting you all to herb and flower U-Pick events when the crops are in.

In the 2025 season many more of the citrus trees that we planted on the slopes of the field will be maturing and giving their first, meaningful crop. Besides Lisbon and Meyer lemons we have planted Buddha’s Hand citrons, Limequats, Kumquats, Finger limes, Thai Limes, Makrut limes, Yuzu limes, Sour Oranges, Blood Oranges, Sudachi, and Assadas citron. Keep an eye on the newsletter for updates on mid-winter citrus theme pop-ups. And coming up soon, on December 7th, from 11am to 5 pm, at the Corralitos Cultural Center, 127 Hames Road, we will be participating in the 2024 Holiday Sip & Shop with a wide range of other local vendors. There will be music and wine. We’ll be bringing seasonal farm goodies, citrus products, herbs, veggies and gifts. Swing by and visit us.

The field on a quiet, damp morning years ago when a large flock of wild turkeys showed up. They’ve never really left, though their numbers go up and down. A turkey gobbling outside my window woke me up this Thanksgiving morning.

Graydon and Gerardo enjoying the spectacle of a large tractor hauling a laser-leveling rig when it got stuck in the field, circa 2001

Samson keeping an eye on me and snoozing as I worked to construct what would become the lavender labyrinth. You can see the young citrus orchard on the slopes. This was sometime during Covid.

A recent drone shot of the labyrinth.

Alexis and I inspecting the lavender crop last year with Green Oaxacan corn on right.

|

-

Looking up the slope from the field towards the farm gate and the house during peak marigold season.

Somethings about farming are universal and timeless, lol. Here’s my dad with a tractor stuck in the mud on some ranch in the Salinas Valley circa 1946.

.

|

Mary’s Gold

Calendula officinalis, the “official” marigold, here pictured growing in our gardens in the spring. This is the preferred herbal variety. We have another, smaller, weedier form that is just as pretty but has smaller blooms. These are “Mary’s Quarters,” so to speak; the weedy forms are more like “Mary’s Pennies.”

Hi All: There’s gold, there’s “fool’s gold,” and then there is “Mary’s Gold.” As I sit down to write you a brief note, I see that gold is trading today at $2742.8 per ounce. We have a lot of “gold,” on the farm, but not this metallic, shiny, valuable kind, so I don’t usually pay much attention to price fluctuations in the precious metals markets.

“Fools gold,” or Pyrite, is a metallic, flakey, mineral that glitters and flashes in the pan. If you find yourself prospecting up along the American River in the Gold Country you might strike “Fool’s Gold. Pyrite isn’t real gold, but”Fools’ Gold” may not just be for fools any longer. Pyrites can contain lithium, which is a material that is increasingly useful (and valuable) to the renewable energy markets for the production of lithium batteries. I don’t have any fool’s gold either. But I’m rich in “Mary’s Gold.” I’ve got lots of marigolds!

Before Mary was born, met Joseph, or talked to Angels, “marigolds” were known to Romans as “Calendulas,” which means “little calendars” in Latin. With its brilliant orange and yellow flowers, the Calendula was much esteemed in the Old World for its putative medicinal properties and its use as an ornamental and culinary plant. A Calendula’s golden petals can be plucked from the flower head and used to color food as a “Poor Man’s Saffron. ” The plant was historically treated as a “pot-herb,” and it found its way into soup pots AND into witches cauldrons. Some people alleged that drinking calendula tea would enable the seeker to see fairies. And across South Asia, the Calendula’s bright orange wintertime blossoms were appreciated since ancient times and used to decorate shrines and honor the gods.

Even when the old, Pagan ways of doing things were upended across Europe by the moral demands of the new, upstart Christian religion, the calendula managed to hold on to its honored place in spiritual botany. Mary, the virgin Mother of Jesus, took on relevance as a cosmic Earth Mother in the new world order. The iconic, celestial blue cloak that Mary wears in so many statues and images represents the heavens that envelopes us all in its starry veil. And, just to bring things back down to earth, the story I heard is that as Mary walks the earth, bringing relief to the suffering, weary people who have faith in her love, marigold plants are sown in the soil by her footsteps. When calendulas sprout and bloom with the winter time rains Mary’s tracks are carpeted with orange, daisy-like, calendula blossoms- her heavenly “coins,” so to speak, that spring from the earth, year after year.

It seems incomprehensible, but these Cempasuchil marigolds, Tagetes erecta, an inheritance from ancient Mexico, are often called “African Marigolds.” No! The Africans invented mathematics, coffee, AND the Blues, but the Mexicans have this marigold to their credit.

I flatter myself to think that Mariquita farm has been visited many times by the Cosmic Earth Mother, because our fields are practically plagued with wild marigolds every spring. It’s pretty to see the green grasses dotted with Mary’s gold but there can be so many wild calendulas popping up that they have to be hoed out for our crops to thrive. When the Spaniards invaded the Americas they brought their arts, their guns, their religion, their livestock, their diseases, and their weeds with them. Some botanists would suggest that the hooked, burr-like seed of the calendula came into California as “stickers” in the tails of Spanish Cattle, but that’s “BS;” lol. I’m going with the Calendula’s presence in our fields as a seasonal manifestation and reminder of a visitation from Mary, Jesus’s mom and the Queen of Heaven and Mexico. forThe wild calendulas on our farm are very happy growing throughout Central California’s mild, coastal climate; it’s just like the Mediterranean conditions that they originally evolved in.

Small farms that produce vegetables for local markets are called “truck farms.” Here’s our truck. I recently gave her a new paint job so that she wouldn’t feel out of place among all the colorful fruits, vegetables, and flowers that we grow.

The Spanish didn’t only take America’s gold bullion back to Europe. Besides gold, the Americas were rich in native crops previously unknown to Europeans. Besides corn, squash, beans, chilies, tomatoes, potatoes, and sunflowers, America’s first peoples developed both chocolate AND vanilla! And the so-called ‘African marigold.'” From Central Mexico down through Central America indigenous religious shrines were decorated with dazzling gold, aromatic, Cempesuchil flowers. It didn’t take long for Spain’s spiritual caste to accept the cempasuchil as a New World “marigold,’ and to employ its orange blooms in festivals like “El Dia de Los Muertos.” And for their part, Spain’s merchants were quick to export these “new” marigolds to Asia, along with the cargoes of stolen gold that they were using to buy the spices of the Indies. The cempasuchil promptly found favor in India as a bold, richly-scented alternative to the old-school calendula marigold. India’s warm, humid, climate proved to be a hospitable environment for the cempasuchil and soon its gold flowers were cultivated on an industrial scale to serve and ornament religious holidays like Diwali.

We will be getting our wood-fired oven stoked up for our Day of The Dead celebration with the Jack O’Neil restaurant.

Just as Central California’s moist, mild winter is amenable to calendula marigolds, so our summers are perfect for growing cempasuchil marigolds. On Mariquita Farm we grow a variety of cempasuchil called “Chedi Orange,” which is a tall, sturdy variety with a flower exactly the same color of orange as a Vietnamese Buddhist Monk’s robes are. We aim to harvest flowers in time for both Dia De Los Muertos and Diwali. These two Holy Days usually fall around the same time of year, so for us, if I can get tiny marigold transplants into the ground by July 25th, I’ll have a nice crop by Halloween that’ll last through Diwali. When the field is in full bloom the effect is spectacular. We pick the flowers to sell either by the bunch or loose, by the 100 count of bagged blossoms, for garlands. It’s been fun to learn my way around this crop, and it’s a joy to be out in the middle of the flowers. We may not have any gold to spare, or even any fool’s gold, but we are the Mother Lode of Marigold! Come see for yourself! We are offering what I believe to be California’s ONLY marigold U-Pick! See the details on the events page of our website, mariquita.com.

The pumpkins are getting ready for their big day!

If you feel more about experiencing the marigolds without having to work you are invited to the Day of The Dead Celebration that we are hosting with our friends from the Jack O’ Neil Restaurant at the Dream Inn in Santa Cruz. Chef Gus has been supporting the farm for a number of years now. He and his team will be preparing a meal that reflects both his kitchen’s seasonal, our farm to your table philosophy as well as the traditional Mexican flavors of this colorful and evocative festival. Come help us compose a floral ofrenda that pays respect to those loved ones who have passed on.

A Day of the Dead Gathering

with Jack O’Neill Restaurant & Lounge

at Mariquita Farm in Watsonville

Saturday, November 2nd, 2024

3:00 – 7:00 PM

Join us for an evening of celebration and remembrance where Esther Vasquez, Jodi Louderback and Nikki Kasprian unveil the rich traditions of El Dia De Los Muertos alongside a delectable meal of traditional dishes prepared by Chefs Gus Trejo and Greg Karjala of Jack O’Neill Restaurant & Lounge at the Dream Inn.

Located in Watsonville, Mariquita Farm offers a beautiful setting for a “Farm to table on the farm” meal cooked for you in a lovely and private garden setting with a lavender labyrinth, a field of marigolds and flowerbeds.

*Due to the nature of the event, we will not be able to provide any dietary accommodations. Meat and vegetarian options will be available.

Experience:

- Personalize the floral altar with a cherished photo or favorite foods of a deceased love one (ofrendas).

- Craft a marigold head crown or gather flowers for your DIY alter at home.

- Explore the milpas (gardens) that nurtured the meal prepared by Chefs Gus and Greg.

- Say hello to our friendly donkeys, Sweetpea and Antonia.

Time: 3:00 to 7:00 pm

Ticket Cost: $100 per person includes dinner and a selection of activities.

|

.

|

Tomato-Palooza/Mariquita Farm Event Schedule

Piennolo tomatoes make fabulous dried tomatoes. Here are some fresh Piennolos getting ready for their trip thru the dehydrator.2. We dry-farm our Piennolo crop so they start out firm and flavorful even before the drying process concentrates the flavor.

Hi All: After a longer wait and a later season than we usually experience, we are happy to announce that our 2024 tomato crop is finally coming on. It’s not too late to plan for your canning and sauce making. Besides our Dry-farmed Early Girls, San Marzanos and Piennolo tomatoes we will also be picking mixed heirlooms and cherry toms. The potato crop is out of the ground and our hard squash crop is ripening too, so we can bring a range of gourds, winter squash, and pumpkins to our pop-up events, along with our seasonal citrus. All of our dried herbs, herbal infusions and herbal salts are on the menu too, along with olive oil from our friends at Belle Farms in Watsonville, California. Here’s a tentative schedule of tomato sales for you to consider. Other dates and places may be added as time, harvests, and opportunities allow:

Saturday, Sept. 28- We “pop up” in front of the Jett & Rose Boutique at 2905a Freedom Blvd, Watsonville.

Sunday, Sept 29 – Come meet up with us in front of Piccino Restaurant in San Francisco’s Dogpatch neighborhood.

Sunday, Oct. 6- We are tentatively set to return to our home away from home in the East Bay on 9th Street in Berkeley.

Monday, Oct. 14 – Palo Alto hosts us Ross Road off the Oregon Expressway.

Friday, Oct. 18- We return to the annual 10th Avenue Earthquake Block Party in San Francisco’s Inner Richmond neighborhood.

Sunday, Oct. 20 – We’re back at Piccino in Dogpatch.

Tuesday, Oct. 29- Visit us at Happy Girl Kitchen at 173 Central Ave, Pacific Grove. They are a great brunch/lunch spot!

Dry-farmed Early Girls on the left, Green Zebras in the middle, and Black Prince tomatoes on the right. The Green Zebras have the brightest acid to sugar balance in this trio. The Black Prince are a good bet for people who want a less acidic fruit, and everybody loves the Early Girls.

Along with our traveling “Tomatopaloozas,” Mariquita Farm will be hosting a series of on-farm events this coming fall, including:

1. U-Pick Marigold/Cempasuchil opportunities, dates TBD depending on the weather, but we’re hoping to host harvest days most Wednesdays or Fridays thru October. Keep an eye on the events page here at mariquita.com.

2. Sunday, October 13th. We host visitors from the Santa Cruz County 2024 Open Farm Tour. Tickets are available thru eventbrite @

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/open-farm-tours-sunday-oct-13-tickets-1007901619877

3. Saturday, November 2nd. Join us for an evening of celebration and remembrance as

Esther Vasquez, Jodi Louderback, and Nikki Kasprian, share

the rich traditions of El Dia De Los Muertos. Chefs Gus Trejo & Greg Karjala from the Jack O’Neal restaurant at the Dream Inn in Santa Cruz will be partnering with us to present a season Mexican inspired meal in the gardens that will be both traditional AND innovative! It will be a colorful and flavorful gathering and I’m looking forward to it.

When I say “Everybody” loves Early Girls I mean EVERYBODY! Here’s Mr. Bull enjoying his share of the harvest. He’s not too particular about bruised or sunburned fruit so he gets the culls.

Besides tomatoes, we’re growing a lot of cut flowers these days and I’m sure we will bring bouquets for casual sale.

I’ll pick a bunch of Lisbon lemons to bring as well, along with any other specialty citrus we have that is ripe. Over the last few years we’ve planted over 200 citrus trees!

Heirloom Rugosa Butternut squash are not the only kinds of hard squash that we will bring to the pop-ups, but they’re my favorite because of their excellent flavor, texture, and keeping qualities.

The pumpkins are getting ready for their big day!

|

.

|

Tomatoes On The Mind

Some mariquitas making themselves at home in a sunflower. I was surprised to see how well sunflowers tolerate cold weather. Next year I’ll make the first plantings a good month earlier than I did this season. It turns out that sunflowers are a great trap crop for Thrips (Thysanoptera) so they a great crop; beautiful, edible, and beneficial for the other crops!

Our Lavender Labyrinth was purple with flowers and humming with bees over the last two months. We welcomed lots of new and old visitors to our farm for our lavender U-Picks during June and July. The lavender crop peaked this year as our lavender plants finally reached maturity and looked full and beautiful.

A lot of the tomato crop is at this stage right now.

A young helper and I hauling a lavender harvest out of the field in the Kubota Mule. Summer Camp @ Mariquita lol

This year’s late spring rains favored the lavender but the persistently cool and wet weather earlier in the year created a situation that has us waiting longer than usual on tomatoes. The soil was too wet to work well in March and, when we were able to turn the ground, it dried out blocky and rough, not fluffy the way the tender little tomato plants like it to be. We had rainstorm after rainstorm with the fronts moving in just frequently enough to keep us from cultivating. The first wave of tomatoes did not thrive, but the weeds did. In the end, we lost the early crop because it would have been expensive to clean and, given the stunted and tortured tomato plants lost in the grassy, lumpy clods, it was not worth the effort. But our second and third crops are doing well and growing according to schedule. The Early Girls and the Heirloom tomatoes will come first, towards the end of August. The Piennolos and the San Marzanos will come last, as always. It’s a drag that it was too wet early on for an early tomato crop, but the good news is that we got plenty of rain, so the dry farming practices that we employ to grow a flavorful tomato will not be as dicey as they can be in a dry year.

These are likely the very first tomatoes that will ripen. I’ll eat them to check for quality.

I know you’re wondering when you will see these tomatoes lining up to jump on your plate, but it will take at least one more spin around the moon before the first fruit is ripe enough to leave the field. An heirloom tomato salad with the colorful slices all drizzled in olive oil and balsamic vinegar, sprinkled with basil leaf paired with slices of fresh mozzarella is our version of summer living. The anticipation is making us antsy but, rest assured, once the tomatoes arrive, they will have been worth the wait. There is nothing like a dry farmed Early Girl or San Marzano to get us up and readying our kitchens for a weekend of canning with friends. As August moves along we will begin to see lots of progress in the tomato crop. We will be doing our tomato pop-ups again this fall and will keep you posted via our newsletter and website (Mariquita.com) on all the places and dates we will be. You can also follow us on @https://www.facebook.com/

The cool, wet, spring favored the citrus orchard we’ve planted at home. Here is Tassa loving up an Assadas Citron.

Mark your calendar for more farm activities scheduled for October. Mariquita Farm will be part of the Open Farm Tours on Sunday, October 13th. https://ticketstripe.com/events/3079105487429197.

Here are the first marigolds of the season.

One of this spring’s projects was the installation of 63 bee hives. Mariquita Farm was chosen to be the “beta site” by “The Bee Bank” to test their innovative hive design. More on this project later as it merits its own newsletter. The bees seem very happy.

I’m almost finished planting out our main crop of marigolds. We will hold a “Day of The Dead” event as well as open the farm up to a series of marigold U-Picks. Follow the newsletter for updates.

Several other local farms & vendors will join us here to celebrate their harvests; look for stalls from Fruitilicious Farm @ https://fruitilicious.eatfromfarms.com/, and @https://www.instagram.com/pricklypoppyfarm/. Prickly Poppy Farm shares the land here with us at the end of our dirt road and Bethany, the Prickly Poppy Pharmer, is our flower mentor. Our friends Arna & Linda from Farm Cat Preserves, as well as Aniko of Farm Chef https://www.instagram.com/p/C7XMSoxPaTN/ will join us as well. They are frequent collaborators and perpetrators, and use the crops we grow in their recipes.

Here on our home ranch you’ll see our crops of citrus, pumpkins, gourds, herbs, and cut flowers. Right now we’re planting the field of beautiful marigolds, the bright orange sacramental variety that is appreciated used in the celebration of Dia de Los Muertos as well as Diwali, which fall next to each other this year, on November 1st and 2nd We will be selling boxes of Marigold flowers for garlands to decorate your doorways and altars and we will be hosting a Dia de Los Muertos celebration here on the farm with a dinner and salute to our ancestors. This is a fun and colorful event that you won’t want to miss.

The other news we have to share is that our farm is hosting a bee research study with The Bee Bank and our fields have been buzzing all summer with their happy bees. The Bee Bank has an innovative design for their hives and a different perspective on how to care for bees and maintain hive health. If you are a bee enthusiast stay tuned for more activities regarding this project.

Thanks, everybody, for your support. Keep an eye on our newsletter to keep up with the events we will host on the farm later this year. We have been busy here and the farm is thriving. We hope to see you all very soon, tomatoes in our hands and smiles on our faces.

|

.

|

Waiting For The World To Come To Me

The Ladybug’s Lavender Labyrinth is coming into full bloom now. There are several varieties of lavender presently flowering, including “Ellagance,” “Hidcote” and “Provencal.”

You don’t get into row crop farming for world travel, that’s for sure! Maybe, if you work for one of the big boys in Salinas, like Taylor Farms, Dole, or T&A, you may travel to Irapuato, in Mexico, or to Chile’s Central Valley to check in on the winter production. If you’re a fresh produce sales manager for a big corporation you might go anywhere on the planet as your company seeks to increase global brand and gain market share. But if you’re an actual dirt farmer, like me, and you drive the tractor, move the irrigation, hoe the weeds, and plant and pick the crops, it can be difficult to get very far from land that sustains you.

Our friend and neighbor/farmer, Bethany, of Prickly Poppy Farm, took this bird’s eye view of the labyrinth with her drone.

I live on a gorgeous piece of rural property, and I don’t regret that a life in farming has usually seen me parked on some remote scrap of ground. They’ve always been gorgeous scraps of earth anyway, like the Gothic Victorian I lived in on the dairy in Marshal with a view of Hog Island on the Tomales Bay and the Pt. Reyes Peninsula in the background, or the trailer on the cattle ranch in Siskiyou County with its majestic, close-up encounter with Mt. Shasta, or the sight of the sun rising in the east at dawn over Mt. Tamalpais from the cabin window on the vegetable farm in Bolinas…Stuck in Paradise, lol… Sometimes I’ll joke with my friends who have traveled the world that “I’ve let the world come to me.” If you consider the folks who have visited the farm when we’ve offered U-Pick events, I ‘m only speaking to the facts.

One nice thing about having visitors drop in from far away places is that they help me see my own place with new eyes, and that’s as good an experience as traveling can give you. Starr and I work on the farm about 6.78 days of the week and when we go out our door into the yard and look around, it’s hard not to focus on the work that HASN’T gotten done. But our U-Pick visitors arrive at the farm and they see what we have done, and their enthusiasm is refreshing. We’re presently holding a series of U-Pick lavender events, and meeting these visiting U-Pickers has reminded me of the people I’ve met in the past and the distant places I’ve never visited.

First, there were the Russians. When we were doing a lot of farming over in the Hollister/Gilroy area we would often hold Tomato U-Picks. I learned that Eastern Europeans take their tomatoes VERY seriously. On the morning of our first tomato U-Pick three vans pulled up, each driven by a Russian mother with her own kids in back, plus a neighbor’s child or two in tow. They were participating in a community tomato canning project, with some women harvesting in the field and others processing the tomatoes back in the kitchen. The harvesting mothers knew exactly what to do, because they’d grown up on farms in Russia. The mothers assembled the kids, handed out the boxes, showed the children how to properly pick tomatoes, and told them to get scampering. As each kid came out of the field their tomatoes were inspected, weighed, and boxed up until, collectively, before the sun had even climbed high in the sky, the three vans of mothers and children had picked over a thousand pounds of perfect, ripe fruit. As they worked, the women chatted in Russian, and while I couldn’t understand a word they said, it was hard not to notice how much they enjoyed being back out in the open countryside once again, with the smell of fresh, ripe tomatoes in the air, but this time THEY were in charge of the harvest, no longer just being the girls getting bossed around. That crew came back every year and, often, on the first warm day in spring, we’d get an email from the head mother, asking as to when the tomatoes would be ripe? If they hadn’t already had careers and situations going for them where they were living on the Peninsula, I’d say these women could easily get into the harvest management business in the Salinas Valley because they had the skills to effectively assemble and motivate a picking crew.

Ellagance is one of the shorter stemmed lavenders, but also one of the brightest, and it is very fragrant.

I’ve never been to India, either. I’ve learned that while many of the East Indians who live in the South Bay and Silicon Valley may have attended the most prestigious universities in India, or abroad, many of them actually started their lives in village India, far from the virtual, logical, international and transformative platforms they live on now. While they may have come to the farm to pick eggplant, basil, or squash, I noticed that many of them brought their kids with them; kids who did not necessarily want to be there.

Can you see the turkeys roosting in the Torrey Pine’s branches as the solstice moon rises? I count at least 5 in this photo, but there were over a dozen turkeys in the yard a minute ago.

“It’s too hot,” I remember one pre-teen telling his mother. The mother and her friend had a big laugh over that.

“No,” they said. “It was hot in the village when it was 43 degrees (Celsius) and there was no air conditioning. This is cool. Pick your grandmother some eggplants.,”

But, as “hot” and “boring” as things could be on the farm, I noticed it was never too long before something interesting and different happened to divert the kids. One year a fire broke out on an adjoining ranch and the Fire Retardant Bombers flew overhead. Another year there was the appearance of a Gopher Snake, three and a half feet long, with all the attendant drama. And there was that time that the sheriff raided an illegal cannabis grow on a next door ranch and there were helicopters and SWAT teams.

Isn’t it amazing how there’s a turkey that is as handsome as me?

Besides “U-Pick” lavender, we will have our freshly dug potatoes for sale.

One year a visitor really surprised me. He was from India and he worked in high tech. He met me in the farmers market and told me that he had a dream of “going back to the land.” I’ve heard that before. This fellow came to several U-picks and asked lots of questions about insect management, water management, weed management, labor management, marketing, and community engagement. He continued to visit me at the market and ask questions about specific crops, about Community Supported Agriculture, about coolers, about fertilizers. The last time I saw him he told me that he had inherited his grandfather’s rural property in India, and that he was leaving high tech and really going back to his family’s roots. He said that he’d observed the curiosity and interest that my Indian visitors had taken in our farm in California, and he was creating a little farm in India that could reach out to urban dwellers who were losing touch with their rural past and engage their interest and hope to help preserve India’s small farm economy. He thanked me for the inspiration. That was a nice thing to hear.

Because I’ve worked with many Oaxacans over the years, word got out that I grow chilacayote, a huge, hard squash which is especially esteemed in Oaxaca and points south through Central America. You can sometimes buy chilacayote in Watsonville in the Hispanic markets but the supply and quality is not reliable. I got a call one day from a woman who wanted to come out to the farm and pick her own chilacayote. She showed up with a nephew to help her carry the heavy chilacayote up the hill.

“This one is REALLY hard,” she explained to me, “Muy macizo!”

“Macizo” was good. She wanted that one; the ones in the tiendita were always too “tiernito,” too young, tender, and undeveloped.” Her squash turned out to be 30#. By the time she was done her nephew had dragged 200# of chilacayotes up the hill. When she came back a year later she brought her daughter and her two grand-children. She loved the farm scene with the corn, squash, beans, flowers, and donkeys because it reminded her of the farm she’d grown up on in Oaxaca. The grandchildren, a boy, aged 10, and a girl, aged 7, were preparing to be bored, especially the 10 year old. We were walking to the chilacayote patch when a wild turkey exploded out of the willow brush in front of us and fled, flapping up a big drama and incoherently squawking in terror.

“Look!” said the sister. “A peacock!”

“You’re stupid,” her big brother told her. “That’s a turkey.”

Besides lavender, we grow a wide range of citrus, flowers, herbs, and vegetables. These are Buddha’s Hand Citrons, bound for Gather Flora LA in the Los Angeles Flower Market.

The granddaughter scowled. She wasn’t happy, but she wasn’t stupid. In Mexican Spanish the word for “turkey” is “guajolote,” from the Nahaul word “huehxolotl.” But, in the Castilian Spanish taught in schools, a “turkey” is a “Pavo.” And, in “proper” Spanish, a peacock is a “Pavo Real,” or “Royal Turkey.” The granddaughter kept scowling, but she was thinking hard.

“I’m going to call it a “MEXICAN PEACOCK!” she declared. Defiant! to the end.

We all had to laugh. …And agree.

Wild Turkeys may look black or brown from a distance, and they camouflage themselves so perfectly that you often don’t even see them from a distance. But, up close, wild turkeys shimmer. They’re iridescent, psychedelic, and weird as hell. When you look in their eyes you can see that they’re broadcasting and receiving on an entirely different channel. Their heads turn colors, they puff up theatrically, they won’t shut up with all the gobbling, and yet they survive. The Mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes, foxes, hawks and owls all eat their babies like popcorn, but yet they persist. Turkeys look like flying dinosaurs. They are easily as trippy a creature as any Peacock ever was. They are always here “U-Picking” and I can’t see them without thinking about the “Mexican Peacock.”

I’m holding a fruit cluster of Cuban Shaddock. If you have a dining room table the size of an airstrip this would work as a centerpiece. I love this plant for its flowers, its scent, and its drama. It also has thorns that could pop a truck tire.

A visiting couple with a modest haul of lavender. They are going to have a fragrant drive back to San Francisco.

Starr’s Farm Store is full of the dried herbs, lavender products and preserves from the farm, plus her collection of other treasures from the earth.

We want this property to be a beautiful, productive garden that is as abundantly full of life as is possible, so I don’t want to bow to tradition and shoot the turkeys, but these “Mexican Peacocks” are annoying. And they’re no more a native than I am, or even less so….The wild Turkeys we have here are descended from wild turkeys that the California Department of Fish And Game brought in from Arizona in the ’50s in an effort to increase sales of hunting licenses, and my family has been here since 1892 when my Danish Great Grandfather dodged the German Army Draft in occupied Schleswig and immigrated to Watsonville. Different times! Now the turkeys run riot. I like that they eat a lot of insects, like ticks, but I’m not thrilled that they peck at my crops. The worst is when they choose to make a dust bath in my planted beds and roll around like Rhinos until their itch is scratched and my sowing is ruined.” And the males are known to fight their reflections in the glass door to Starr’s farm store and make a mess on the porch.

So the turkeys are tolerated, but you are welcome to visit and pick your own lavender. The splendid lavender labyrinth is worth the trip in itself, and we will have farm produced citrus, potatoes, herbs, and flowers available for sale as well. We have several nice picnic spots for people that want to relax for a while with the birds and the bees. Bee sure to check our website @mariquita.com and register to visit soon. We will be hosting Lavender U-Picks through July 26th. We hope to see you. Thanks, Andy & Starr

.

|

Never Turn Your Back On A Bull

Soda Lake, in the Carrizo Plain National Monument, is often dry for for long periods of time.

A recent visit to the Carrizo Plain National Monument got me thinking about sex, violence, and botany. If you’re still unfamiliar with the Carrizo Plain, know that it sits astride the San Andreas Fault, tucked in between the Temblor Range to its east and the Caliente Range on its west. “Temblor” means “earthquake” in Spanish and “Caliente” means “hot,” so you can make a pretty good guess as to what usually goes on out there. Maybe you’ve traveled down I-5 to LA from the Bay Area along the westside of the San Joaquin and looked out the window at the empty, bald, hills off in the distance. That landscape is usually a baked, drab, dun color, but for a few weeks each year- if the land has been blessed with any rain- the hills and plains can be a bright, grassy, green splashed with a psychedelic array of brilliant yellows, oranges, purples and blues as wild flowers explode in glory. I’ve been going out to the Carrizo off and on since I was a child because my father was a native plant botanist, and it was he who first told me, “Never turn your back on a bull.”

In the aftermath of a 2017 LA Times story on a Carrizo “super bloom,” it seems as though half the world has found out about this relatively recent addition to our National Park System and, when the wild flowers do happen, a visitor may even experience an incongruous LA style traffic jam on the typically lonely Soda Lake Road, a good twenty miles of which is still just a dirt track across an empty land. My father didn’t need a colorful wildflower display to attract his attention. The Carrizo Plain is almost a desert, and it is an “endorheic basin,” which means it is a sink with no drainage. What water that does fall onto or flow into the Carrizo Plain puddles up in Soda Lake. But the water soon evaporates and Soda Lake is usually no more than a baked, dry, salt playa. The Carrizo Plain is too droughty and remote to be of much use agriculturally, in stark contrast to the neighboring San Joaquin Valley, which is one of the most intensely managed agricultural valleys in the world. For California native plant botanists, like my father, the Carrizo Plain represents one of the last opportunities to study an environment that approximates the now extinct native ecosystems of California’s Central Valley. Dad began going to the Carrizo when he was a grad student at UC Berkeley beck in the mid-1950s, long before the land was framed as a national monument, and when the idea of a traffic jam on Soda Lake Road would have been insane.

Cattle still range across sections of the Carrizo Plain.

Today, as you enter the monument on Soda Lake Road from the north, you cross a cattle guard and there is a yellow road sign with an iconic image of a cow, intended to alert the driver that there may be range cattle crossing the road ahead. I’m sure that sign didn’t exist back in the fifties, but if dad had seen it he would have smiled. My father grew up on dairy ranches up and down the Salinas Valley and he knew as much about cows as he wanted to. Anyway, the prominent outline of a huge, swollen udder identifies the creature on the sign as a milk cow, which is funny because milk cows are just about the last creatures you’d be likely to see on a seared and scant range like the Carrizo Plain. The rough and rowdy breeds of beef cattle that can sniff out distant waterholes and lick up enough dry grass to survive on an open range are quite different animals in physique and behavior than their placid dairy cow cousins. Dairy cows are like sports cars that must be given the best fuels to perform; they beg to be fed with leafy bales of alfalfa, and they must have LOTS of water available if they are to make all that milk. Dairy cows are generally docile by mature. It is interesting, though, that dairy bulls have a reputation for being quick to anger and prone to violence.

Dad did have a story about a kid he knew on one of the ranches he grew up on who dreamed of escaping the smelly routine of life on a dairy for the excitement and glory of the rodeo arena. The unfortunate boy thought that he’d practice for the big time by riding a Holstein bull in the dairy pen. The kid perched himself on the roof of a shade shed until he had a chance to drop himself onto the back of a passing bull as it headed out into the sun to eat, whereupon he was promptly thrown to the ground and gut stomped to death. Never turn your back on a bull, and definitely DON’T get on a bull’s back! Bull riders at the rodeo may be incredible athletes, but they are crazy to the bone.

A lovely stand of Phacelia rimed with frost, photographed just after dawn at the south end of Soda Lake.

Many consumers think that if a bovine critter has horns then it’s a bull. Not so! Female cattle usually have horns too, if they haven’t been cut off or burned out of their infant skulls in the bud. Male deer, or bucks, have antlers and female deer, or does, don’t. An antler is different from a horn. A buck will shed its antlers at the end of the rutting season. True horns are bony structures that are part of the skull. A cow can come into heat at any time of the year and a horny bull will always be ready to breed her. It’s not for nothing that a crude and popular term for the condition of being sexually excited is to be “horny.” A healthy bull is always ready to mount a cow or a…..When I was a teenager working on the Bell Ranch in upper Carmel Valley, two new, purebred, Angus bulls were delivered. The young bulls would be quarantined for a couple of weeks before being introduced to the herd so that we could be sure they didn’t harbor any communicable diseases. The bulls were excited after their bumpy trip in the livestock trailer and one bull mounted the other. “Will he be interested in cows?” I asked. The cowboy who had just unloaded the pair laughed. “Look, kid, ” he said. “That bull is so horny he’d screw a knot hole.” An indelicate observation, perhaps, but not inaccurate.

This young bull of mine was tame, as bulls go, but you should never turn your back on a bull. They aren’t dumb, but they can easily forget that they have been “domesticated.”

Cattle are ruminants. That is, they have four stomachs and, after walking about the landscape and grazing, they will cough up the grass they’ve just consumed from their first stomach, the rumen, and settle down to “chew their cud.” As they chew away and “ruminate” cattle look introspective and peaceful, which has led some writers to use the verb “ruminate” to mean “to think deeply.” I’m not saying that bulls are not capable of having deep and philosophical thoughts, but even a ruminating bull can be moved to a display of fierce, primal violence in a heartbeat if provoked. A bull’s skull is so very thick and their gaze can be so inscrutable that we can’t ever know what exactly is going on mentally between their horns. It’s a good practice to keep oneself a respectful distance even from a ruminating bull and “let the mystery be.” Dad knew all this when he turned his blue Ford sedan down lonely Soda Lake Road back in the mid fifties, his new wife riding shotgun, and headed out into the boonies to look for rare, endemic milkweeds.

My father as a young man in the Salinas Valley. There’s an irony at play in this photo. Maybe the tractor was stuck in the mud, but he wasn’t, and he’d soon flee ranch life for a career in academia. I, by contrast, have a genius for atavism, and I would flee a life on a scientific field station for a career of getting stuck in the mud on a series of farms. Go figure….

Soda Lake may usually be dry, but every once in a while it has standing water in it. Last week, when we visited, we saw a real lake with water and ducks. More often, Soda Lake boasts a crust of white salt on top of a slurry of sticky mud. Even when the lake bed is dry from its sun baked surface all the way down to hell it’s still not a good idea to drive off the road. It is easy, even for a four wheel drive vehicle, to get stuck in Soda Lake’s crunchy, slimy salt. It’s a long road. And narrow. When you are driving it you can really get a feel for the wide open spaces of the Old West, and you feel glad you’re not walking. The middle of Soda Lake would be a terrible place to get stuck or break down. The nearest tow truck, even today, would be hours away and back then, of course, there were no cell phones. The sedan kicked up a little cloud of salt dust as it rolled down the narrow road and the odometer scrolled the miles away.

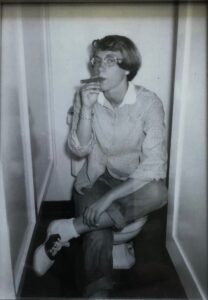

My mother as a young woman, clowning with a cigar in a bathroom at UC Berkeley. Dig the Saddle Oxfords! So chic!

Yes, it may have been a long trip, and the morning might have been heating up past the comfort zone as the sun rose higher in the sky, but dust, a sore butt, and annoying heat are just some of the personal sacrifices that botanists (and their partners) must expect when they set out on a quest to find rare, endemic milkweeds. And milkweeds really are worthy of attention, even if they are not flashy like orchids or scented like roses. Milkweeds host Monarch butterflies, and without them the Monarchs cannot survive.

My father was in that generation of plant ecologists who were moving past the era when doing botany meant going into a “dark continent,” “discovering” a plant that the “natives” had known about since God, and then naming it after themselves. Academic colonialism was giving way to a new, more holistic, interdiciplinary approach to scientific inquiry which sought to explore the web of life and the interconnectivity of all living organisms. “Woke” botany? The Carrizo Plain may not have a flashy waterfall like Yosemite, or a spurting geyser like Yellowstone, but the dry hills and the dusty flatland have secrets to reveal.

Mom and dad were most of the way across the lakebed and nearing the grasslands when they saw a large, dark object in the road ahead. As they draw close they observed that their path was blocked by a big, black Angus bull, apparently asleep. Dad approached but stopped the car at some distance, expecting the bull to wake up and move out of the way. But the bull was content to snooze in the warm sun. He had all the time in the world to ruminate on deep thoughts.

Dad honked his horn.

The bull opened one eye, but he didn’t move. What does scientific inquiry into the interconnectedness of all living beings matter to a 1800 lb, drowsy, black bull on a vast salt flat? Maybe later he would walk to to the hills, eat some grass and check in on his harem of cows. But for now…..snore….

Dad honked again.How annoying! The bull opened one eye and observed a humble, blue, Ford sedan. He swished his tail. The morning had been more pleasant when it was just him and his halo of flies, thinking his deep thoughts and chewing his cud.

Dad didn’t have all day to wait. Mom was hot and tired. They didn’t dare drive around the bull for fear of getting stuck in the loose, slimy salt. Dad edged the car forward and honked again. This was too much for Mr. Bull. He was the black Lord of the Plains. He ceded his path to nobody, man or beast. He’d been peacefully enjoying his “alone time” but now that the tranquility had been disturbed by this meddlesome couple and their absurd car he’d show them who was boss. The bull lumbered to his feet in rage to face his new enemy. The world would soon see who turned tail and ran.

The bull lowered his head. Dad put the car in reverse; he couldn’t turn his back on the bull because if he tried to turn on the narrow dirt track he’d likely get stuck in the salt and be stranded miles from anywhere with a new wife while a mad bull pummeled and gored his sedan.

The bull lowered his head. Dad put the car in reverse; he couldn’t turn his back on the bull because if he tried to turn on the narrow dirt track he’d likely get stuck in the salt and be stranded miles from anywhere with a new wife while a mad bull pummeled and gored his sedan.

The bull charged. Dad hit the gas. Bulls move fast. Of course, a Ford can go faster than a bull under laboratory conditions, but backing up at high speed on a narrow, dirt road is a nerve racking proposition. I’m here to tell this story, so obviously my parents escaped the wrath of the Lord Of The Plain to tell me the tale, but I smile when I see the yellow diamond shaped sign with the placid dairy cow and the words, “Impassable during wet weather.” It is rarely wet on Carrizo Plain, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that the road is passable on a hot, dry, summer day.

There will be no bulls attending our Saturday, May 4th, celebration of World Labyrinth Day. Yes, I know that the original Labyrinth was created by Daedalus and Icarus for King Minos of Crete to constrain his bull headed monster, the “Minotaur.” The story of the Labyrinth is another of those foundational, mythic tales of the Western tradition that the moralistic book-burners among us would ban if they ever chose to read Classic Western Literature. It’s said that Pasifae, the daughter of the sun, brave Helios, out of an ocean nymph named Perse, grew up to be the Queen of Crete, and by some accounts she was also a powerful sorceress. But Pasifae, herself, was put under a cruel love spell by Aphrodite, which provoked in her heart a powerful sexual lust for that perfect, white Creten bull that her husband, King Minos, kept in his royal herd. To realize her amorous intentions, Pasifae contracted with Daedalus to build her a wooden, cow-shaped crate with a glory hole at one end. You’ve heard of the “Trojan Horse?” Well, this was the “Cretan Cow.” Daedalus draped his construction with a cow hide to approximate the scent of a bovine in estrus and Pasifae backed into her love shack. The Royal corral gate was opened, the perfect white bull entered the pen, and one thing led to another. In due course, Pasifae gave birth to a bull-headed male child, named Minotaur. “(Mino” for Minos, the cuckold king, and “taur” for Taurus, which means “bull,” as in the constellation, Taurus.) King Minos was NOT happy and he incarcerated the half bovine bastard in the Labyrinth. But our labyrinth is peaceful and inviting. We followed the outline of the labyrinth that was constructed in the Middle Ages at Chartres Cathedral when we created ours. World Labyrinth Day is a moment that people observe all around the world by a silent, meditative walk in a labyrinth as an expression of hope for peace.

If you can’t make it to the farm for World Labyrinth Day consider coming down for one of our seasonal workshops, like our Create A Garden Stepping Stone event on Saturday, June 8th which includes a labyrinth walk.

The Carrizo Plain in 2023 with more flowers but no water in the lake.

Range Cattle in the Temblor Range. The Carrizo Plain National Monument uses range cattle as a tool to remove annual Mediterranean grasses which are “weeds” in the context of preserving native California plant species.

Hi: I’m a cow, not a bull, and I have horns.

.

|