Letters From Andy

Ladybug Letters

Grateful

Thanksgiving marks the end of the season for the farm in a way that New Year’s Day simply does not. Apart from sowing a few beds of quick turnover crops in the protected cover afforded by our greenhouse, our planting schedule is always suspended from Thanksgiving until the first of the year. The days are so short and the nights are so cold at this time of year that anything we plant now will not mature any sooner than the same crops planted after the New Year, so why bother planting, watering and weeding? It’s smarter to wait and plant in the new Year. The crops we’re harvesting now through February were all planted back in August and September so the die is pretty much cast by Thanksgiving. And by March we’ll be picking the crops we will sow in January. For the next month or so we can count on a period of relative calm; busy for the hours we’re working, but not crazy busy, and the more relaxed schedule gives us time to think about next year- and to give thanks for the help we’ve received this year. It’s been such a crazy year and I’m grateful we made it this far.

We want to thank you, because without your patronage we’d be out of business. And we owe the pick-up site hosts a big “thanks” for their generosity in sharing their homes and business with us so that we can share our harvests with you. And I want to single out Victoria Libin for a special note of thanks. When the initial Covid shutdowns shuttered the restaurants that we counted on to buy a lot of our produce we were in a tight spot financially since many of them were unable to pay their outstanding bills promptly, leaving us without the cash flow to continue. Because Victoria was familiar with the restaurant business she saw the problem developing from afar and called me to offer to help bankroll production to keep us going. It didn’t turn out that we needed the help, but her timely call gave my spirits a real boost, just knowing that there are folks out there who have our back. Thanks, Victoria. And a big thanks to Thomas McNaughton of the Netimeas Restaurant group. Thomas presides over three restaurants in SF: Flour and Water, Central Kitchen, and Flour and Water Pizzeria. He’s been hit hard by Covid, and his response has been very community minded and he’s opened up his Central Kitchen space to farms so that they could have a place to distribute their produce to their supporters. Thanks, Thomas.

We want to thank you, because without your patronage we’d be out of business. And we owe the pick-up site hosts a big “thanks” for their generosity in sharing their homes and business with us so that we can share our harvests with you. And I want to single out Victoria Libin for a special note of thanks. When the initial Covid shutdowns shuttered the restaurants that we counted on to buy a lot of our produce we were in a tight spot financially since many of them were unable to pay their outstanding bills promptly, leaving us without the cash flow to continue. Because Victoria was familiar with the restaurant business she saw the problem developing from afar and called me to offer to help bankroll production to keep us going. It didn’t turn out that we needed the help, but her timely call gave my spirits a real boost, just knowing that there are folks out there who have our back. Thanks, Victoria. And a big thanks to Thomas McNaughton of the Netimeas Restaurant group. Thomas presides over three restaurants in SF: Flour and Water, Central Kitchen, and Flour and Water Pizzeria. He’s been hit hard by Covid, and his response has been very community minded and he’s opened up his Central Kitchen space to farms so that they could have a place to distribute their produce to their supporters. Thanks, Thomas.

She probably didn’t know what she was getting into when she got tangled up with me, but my partner, Starling, deserves a lot of thanks. When Covid hit and we couldn’t afford much help she jumped in and helped jump start the farm for a new chapter. She started by reorganizing the packing shed so that the two of us could do the packing by ourselves, and she’s been relentlessly enthusiastic, even when I’d get discouraged. And she’s packed A LOT of boxes. Thanks, Starr.

She probably didn’t know what she was getting into when she got tangled up with me, but my partner, Starling, deserves a lot of thanks. When Covid hit and we couldn’t afford much help she jumped in and helped jump start the farm for a new chapter. She started by reorganizing the packing shed so that the two of us could do the packing by ourselves, and she’s been relentlessly enthusiastic, even when I’d get discouraged. And she’s packed A LOT of boxes. Thanks, Starr.

Shelley wasn’t planning on having a crazy 2020, but it happened anyway, and she worked overtime to help get the farm up to speed for all the new problems. Besides handling all the daily sales she also took the lead in getting us a whole new website and e-commerce platform so that we could survive in the new Covid world. (Shout out to Travis and Kim at Aptos Village Creative!) And Shelley’s persistent good will and attention to detail is always welcome, even when we’re not in a plague scenario. Thanks, Shelley.

And then there are all of the so-called “essential” workers to thank. Yes, they were essential in this Covid year of 2020, but they’ve ALWAYS BEEN ESSENTIAL even when so many people didn’t notice and I’d like to thank them by name. Seeds don’t plant themselves, vegetables don’t hop in the box, and the cartons of produce don’t trot themselves to market; people do the work, and this year more than most, the people doing the work have had to put themselves at risk to get the job done. I’d like to recognize and thank Abisai, Jose, Nataneal, Maria, Gayle, Jovito, Elias, Eliza, Rodney, Fidel, Carmen, Federico, Claudia, Neftali, Gildardo, Rebeca, Ramon, Maria, Luis, y Efrain. Thanks. Gracias.

We wish you a peaceful and happy and healthy Thanksgiving. Once the holiday is past I’m going to get started planting for years 2022 and beyond! I’ve got another 60 young citrus trees to plant — more Bearrs limes, some Rangpur limes, Yuzu limes, plus some Sudachi, a few citrons, and a few more lemon. And I’ll do some picking. The citrus I planted several years ago are now yielding so I’ll be picking a crop of lemons to take to our friends at Happy Girl Kitchen so that they can make marmalade for us. 2021 is going to have some sweet moments no matter what else happens.

We wish you a peaceful and happy and healthy Thanksgiving. Once the holiday is past I’m going to get started planting for years 2022 and beyond! I’ve got another 60 young citrus trees to plant — more Bearrs limes, some Rangpur limes, Yuzu limes, plus some Sudachi, a few citrons, and a few more lemon. And I’ll do some picking. The citrus I planted several years ago are now yielding so I’ll be picking a crop of lemons to take to our friends at Happy Girl Kitchen so that they can make marmalade for us. 2021 is going to have some sweet moments no matter what else happens.

Thanks again from all of us here at the farm!

Andy

© 2020 Essay and Photos (except as noted) by Andy Griffin.

Photo of Gayle at Piccino Mystery Thursday by Debra Baida.

Photos of Ladybug host sites by Gayle Ross.

Radish

The Latin word, “radix,” meaning “root,” is the “root word,” so to speak, for our modern word “radish,” as well as the related mathematical term “radical,” the political adjective “radical,” and the technical botanical noun “radical.” Today we’ll stay grounded in the kitchen and discuss the roots we eat.

I remember a woman who stopped by my farmers’ market stand in San Jose many years ago. She looked at a large pile of bunched radishes that I had heaped up. “Those look awfully small for beets,” she said, “but they’re a pretty purple color.”

“They’re not beets, I replied. “They’re ‘Plum Purple’ radishes. It’s a Japanese variety. The flavor is the same as a red radish, but Plum Purple radishes stay nice and crunchy and mild, even when they get quite large. And the Japanese appreciate the greens as a leafy vegetable for cooking up or putting in soups, so you can see the leaves are long, tender, and smooth.”

“They’re not beets, I replied. “They’re ‘Plum Purple’ radishes. It’s a Japanese variety. The flavor is the same as a red radish, but Plum Purple radishes stay nice and crunchy and mild, even when they get quite large. And the Japanese appreciate the greens as a leafy vegetable for cooking up or putting in soups, so you can see the leaves are long, tender, and smooth.”

“Radishes are supposed to be red,” she said. “A purple radish? I could never try that.” And she scurried off.

“Wow,” I thought. “She doesn’t like to be challenged to try anything new in the kitchen.” Every culture has certain foods that they esteem more than others. Here in the United States we’ve made a popular fetish out of our tomatoes; seed catalogues show off an amazing spectrum of heirloom tomatoes in all their myriad colors, we prize our beefsteak tomatoes for how big they get, our gardens showcase many varieties of cherry toms, we have our favorite tomatoes for sauces, and salads, but when it comes to radishes many Americans are not yet so sophisticated.

The Plum Purple radishes on my market table didn’t stay lonely and rejected for long. San Jose is home to an amazing diversity of people and the purple radishes with the big, tender, leafy greens were soon snatched up. My experiences in farmers markets taught me that Asian cultures in particular value radishes and that there are just as many varieties of radish available to plant as there are tomatoes. In an effort to widen my own farm’s appeal to a broader public I began to plant more radishes and read up about them in cookbooks. And the more I read about radishes the more surprised I was. It turns out that the long rooted form of what we today call the “Black Spanish” radish is one of the earliest kinds of vegetables that farmers ever developed, and it may be the most ancient vegetable crop that is still cultivated in its original, antique form. Before the black radish was “Spanish,” it was Egyptian, and laborers who built the pyramids ate them daily.

The Plum Purple radishes on my market table didn’t stay lonely and rejected for long. San Jose is home to an amazing diversity of people and the purple radishes with the big, tender, leafy greens were soon snatched up. My experiences in farmers markets taught me that Asian cultures in particular value radishes and that there are just as many varieties of radish available to plant as there are tomatoes. In an effort to widen my own farm’s appeal to a broader public I began to plant more radishes and read up about them in cookbooks. And the more I read about radishes the more surprised I was. It turns out that the long rooted form of what we today call the “Black Spanish” radish is one of the earliest kinds of vegetables that farmers ever developed, and it may be the most ancient vegetable crop that is still cultivated in its original, antique form. Before the black radish was “Spanish,” it was Egyptian, and laborers who built the pyramids ate them daily.

I learned that there are radishes cultivated for their seeds which are pressed into cooking oils. There are radishes that are grown for their edible, crunchy green seed pods, which are cooked as vegetables. There are radishes grown specifically for their leafy greens that are harvested and bunched, like mustard greens, and there are radish varieties that have been developed to be used as cover crops, never eaten, but designed to be tilled under to revitalize the soil. And then there are the radishes that are grown for their edible roots. If you’re a home gardener and you want to try some of these more exotic radishes you should check out the Kitazawa Seed Company in Oakland, California. (seeds@kitazawaseed.com) Their most recent catalogue that I’m flipping though now lists 45 different radish varieties! I guess that’s not too surprising. The Kitazawas are Japanese Americans, and the Japanese in particular have a deep appreciation for radishes.

I’m smiling now, because I’m remembering a lovely fall morning several years ago when my friend, Toku, came to visit me at the greenhouses that I rent from the Nagamine family. Toku brought a friend with her who was visiting from Japan to visit my farm and the two women were chatting in Japanese when my landlord, Senior Nagamine, came out of a greenhouse where he was growing a crop of daikon radish. Mr Nagamine is in his mid 90s, but farming has kept him young at heart. Hearing the two women speaking Japanese put a smile on his face and he greeted them warmly. After some initial salutations and introductions he invited us all to inspect his daikon crop. Toku and her friend were charmed and delighted- two farm visits would be twice as fun!

I’m smiling now, because I’m remembering a lovely fall morning several years ago when my friend, Toku, came to visit me at the greenhouses that I rent from the Nagamine family. Toku brought a friend with her who was visiting from Japan to visit my farm and the two women were chatting in Japanese when my landlord, Senior Nagamine, came out of a greenhouse where he was growing a crop of daikon radish. Mr Nagamine is in his mid 90s, but farming has kept him young at heart. Hearing the two women speaking Japanese put a smile on his face and he greeted them warmly. After some initial salutations and introductions he invited us all to inspect his daikon crop. Toku and her friend were charmed and delighted- two farm visits would be twice as fun!

Did Toku like daikon, Mr. Nagamine asked? Of course Toku likes daikon. So Mr. Nagamine stooped over to pull out a fat, long, white daikon root from the ground. The radish was a good twenty inches long. Senior inspected it carefully. Unfortunately, near the tip of the root he discerned a bit of root maggot damage- just a tiny bit, to be sure- but Mr. Nagamine prefers that the produce he sells, and especially the produce he gives to guests be flawless. These days Mr. Nagamine focuses his growing operation on the production of organically cultivated traditional Japanese vegetables, specializing in the varieties he grew up with as a child in his home village of Kagoshima, Japan, but for many years of his life he grew cut flowers. If the customer expects the rose or carnation or the chrysanthemum to be perfect, why should they settle for anything less with the radish?

So he pulled another giant radish from the ground. This one too displayed a tiny imperfection. He was about to pull a third up when Toku stopped him. These radishes would do just fine, she said, and the imperfections were only a reminder of how the crop was grown naturally with no pesticides. Mr. Nagamine stopped pulling up radishes, and he was happy that his two visitors were happy, but he did apologize because this daikon crop was actually a Korean variety, and not the Japanese kind his guests deserved and that he usually planted. We all had a laugh at that, but it reminded me how the Koreans too are a culture that takes their radishes very seriously.

So he pulled another giant radish from the ground. This one too displayed a tiny imperfection. He was about to pull a third up when Toku stopped him. These radishes would do just fine, she said, and the imperfections were only a reminder of how the crop was grown naturally with no pesticides. Mr. Nagamine stopped pulling up radishes, and he was happy that his two visitors were happy, but he did apologize because this daikon crop was actually a Korean variety, and not the Japanese kind his guests deserved and that he usually planted. We all had a laugh at that, but it reminded me how the Koreans too are a culture that takes their radishes very seriously.

This week in your harvest box we’re including some Korean purple daikon. These radishes are very beautiful and mild flavored. They can be used in salads, and I like to slice them into thin coins and dress them with just a squeeze of lime juice. But they’re versatile. These daikon could be used in soups, cut and cubed and roasted, stir fried, pickled, shredded for slaw, and even juiced. I’ve even seen artists carve them into beautiful shapes, transforming these simple smooth roots into flowers, koi fish, and purple swans. They will also keep for a long time in the refrigerator if you don’t need a salad, a soup, a pickle, a stir fry, or a purple swan. Over the course of the cooler months we’ll see a variety of different radishes as each variety comes into its best season. By April 15th the radish concert will have been played through and we’ll begin planting our tomatoes. When we know all the vegetables the world has to offer we can have a fun food fetish for every season!

This week in your harvest box we’re including some Korean purple daikon. These radishes are very beautiful and mild flavored. They can be used in salads, and I like to slice them into thin coins and dress them with just a squeeze of lime juice. But they’re versatile. These daikon could be used in soups, cut and cubed and roasted, stir fried, pickled, shredded for slaw, and even juiced. I’ve even seen artists carve them into beautiful shapes, transforming these simple smooth roots into flowers, koi fish, and purple swans. They will also keep for a long time in the refrigerator if you don’t need a salad, a soup, a pickle, a stir fry, or a purple swan. Over the course of the cooler months we’ll see a variety of different radishes as each variety comes into its best season. By April 15th the radish concert will have been played through and we’ll begin planting our tomatoes. When we know all the vegetables the world has to offer we can have a fun food fetish for every season!

© 2020 Essay and Photos by Andy Griffin.

You say ‘tomato.’ I say ‘tomato.’

Concerning the Piennolo tomato, there’s a noted Bay Area restaurateur who shall go unnamed because, despite my present state of mild annoyance, he is a charming individual, smart and creative, who pays his bills, and has always been generous to me and my farm. But the dissonance- I wouldn’t call it a conflict- between our perspectives does make me think about the roles that marketing, advertising and “branding” play in our lives.

At its best, advertising is simply story telling. Granted, advertisements are stories told in the service of commerce, because a “happy ending” has the consumer buying into the plot line by purchasing the targeted product, but there’s no reason that an ad has to be full of lies. An effective promotional campaign can even be a vector of useful information. With the Piennolo tomato there is a compelling narrative for the salesman to recount that pushes plenty of happy buttons; traditional family values, bright flavor, simpler times, rustic charm, Grandma’s kitchen, country living etc…As it was promoted to me by the restaurateur in question the story goes something like this:

There is in Italy a delightful, open-pollinated, traditional variety of tomato known as the “Piennolo.” Not only are the Piennolo’s small, firm, fruits packed with flavor, the plant is indeterminate, meaning that the fruit set occurs over a long season, not all at once as the determinate tomatoes do. Modern tomato varieties that have been developed for mechanized agriculture are typically determinate so that the growers only need to run their mammoth harvest machines through a field once. To accommodate their production contracts large scale operations will plant sequential crops of determinate tomato crops that roll off, one after another, to accommodate the schedules of the canneries or the marketing commitments of the retail distributors. Machine harvesting is efficient, but there are costs, and sometimes flavor is the price the consumer pays for cheaper food.

There is in Italy a delightful, open-pollinated, traditional variety of tomato known as the “Piennolo.” Not only are the Piennolo’s small, firm, fruits packed with flavor, the plant is indeterminate, meaning that the fruit set occurs over a long season, not all at once as the determinate tomatoes do. Modern tomato varieties that have been developed for mechanized agriculture are typically determinate so that the growers only need to run their mammoth harvest machines through a field once. To accommodate their production contracts large scale operations will plant sequential crops of determinate tomato crops that roll off, one after another, to accommodate the schedules of the canneries or the marketing commitments of the retail distributors. Machine harvesting is efficient, but there are costs, and sometimes flavor is the price the consumer pays for cheaper food.

The Piennolo tomato is not only indeterminate, it’s also quite sturdy, and it can yield a tasty harvest even long after other, more commercial, varieties have dropped dead from mildew. The Italian peasant farmers that first cultivated the Piennolo learned to pull their plants from the ground before the first frosts and hang them from the rafters of their cottages. As the green Piennolo plants withered, even the last green fruits on the vine would slowly turn red, so the cook of the house need only reach up over her head to pick some tomatoes, made all the more flavorful by being so luxuriously late. (Yeah, I wrote that; maybe it could be “his” head but I always heard that it was Grandma doing the cooking)

Ok; so that’s great. My friend, the restaurateur, was hoping I’d grow this tomato for him. It could be a great crop for everybody. He could have a lovely, distinctly Italian tomato to sex up his menu deep into the fall. The diners would get to appreciate true, traditional Italian cooking that they’d otherwise never be able to taste without going to Italy, and I’d get a new product that I could sell late into the fall and keep my cash flow pumping after the main tomato crop had been turned under. I was interested, so I hit the books and I did some online research.

Slightly different versions of The Tale of the Tasty Piennolo were not hard to find online. So I poked through my seed catalogues. Try as I might I could not find seed for Piennolo tomatoes. The closest I came was a tomato called the Principe Borghese, which looked the same in photos as the Piennolo. I bought some Principe Borghese seed and planted it.

Like the fabled Piennolo, the Principe Borghese was a strong plant, apparently resistant to just about every disease. The variety thrived under a dry-farm regimen, requiring no irrigation whatsoever to produce an indeterminate crop of small, firm, flavor-packed tomatoes deep into the late fall. And, like the Piennolo, Principe Borghese sported a curious nipple at the end of its small, cherry tomato sized, almost pear shaped fruit. I liked this tomato a lot, and was excited to show it to the restaurateur who had suggested the Piennolo to me.

My customer friend’s chef de cuisine liked the tomato too, but not enough to buy any. “If it’s not a Piennolo, it’s not going to work on our menu,” he said. I understand branding, so I understood where he was coming from. The restaurant wanted to promote the dishes that they’d planned for the Piennolo and they had a story they were excited to tell. Maybe the Principe Borghese looked and tasted like the Piennolo but when you’re putting your reputation on the line and you’ve got snarky critics to satisfy you wouldn’t want to go with an off brand tomato. So I harvested my crop and introduced the Principe Borghese to my customers, to people like you.

I kept looking for Piennolo seed, season after season. And I kept growing Principe Borghese. I kept offering them to my friend’s kitchen. And I kept on thinking that the Principe Borghese really was just the Piennolo tomato under a different name. I considered just calling my Principe tomatoes “Piennolos,” to get the sales, but as much of a hustler as I am, I didn’t want to be the guy in the parking lot selling fake Rolexes.

I kept looking for Piennolo seed, season after season. And I kept growing Principe Borghese. I kept offering them to my friend’s kitchen. And I kept on thinking that the Principe Borghese really was just the Piennolo tomato under a different name. I considered just calling my Principe tomatoes “Piennolos,” to get the sales, but as much of a hustler as I am, I didn’t want to be the guy in the parking lot selling fake Rolexes.

So then last fall, my friend, Annabelle, called. She had some Piennolo seed just arrived from the Boot. Did I want any?

Well, yes I did. Annabelle’s offer made me glad that I hadn’t “rebranded” some knock off cherry tom as a “Piennolo.” She’s always been the person I knew with the best, truest, varieties of traditional crops and I wouldn’t want her to catch me cheating.

So this year I planted the true Piennolo. And you know what? They are EXACTLY the same as the Principe Borghese, not “like” the Principe- they’re the same plant. Are we in some sort of Champagne scenario where you can’t call the tomato the “Piennolo” if it’s not grown on the slopes of Etna? Are they changing the Tomato’s name at Ellis Island? Or maybe the Piennolo’s different American name is due to some sort of witness protection program kind of situation? So now I’m kind of cross; I finally have a tomato- the same tomato- that I can produce for my customer, and Covid has destroyed this season’s restaurant business.

So now I only have you. You and your home cooking have kept our farm plugging along since 1998. And I’m grateful. We’ve tried to keep our place at your table by growing the tried and true, and we’ve tried to maintain your interest, and our own, by offering some new and different crops. So here’s an old crop with a new name, or at least a different name, and now you know why. No, I’m not going to pull up the plant so that you can hang them from your rafters. You may not have rafters, and anyway it would be a mess to ship. But we will have some late Piennolo tomatoes for you. There was a slight frost last night, so the end of the tomato season is near, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the last Piennolo tomatoes are still good to eat even after the election. Now make sure you vote, and please VOTE TO GET THIS OFF BRAND MUSSOLINI OUT OF THE WHITE HOUSE!

© 2020 Essay by Andy Griffin. Photos (except as noted) by Andy Griffin.

Top right photo of Piennolo (or are they Principe Borghese!?) by Shelley Kadota.

At Home with Ambiguity

If you’re not “at home” with ambiguity, surprises, and triage as a lifestyle, then farming probably isn’t for you, but even by that measure 2020 has been extra special. Now, as the days get shorter, the nights get cooler, and winter lies just over the horizon, it’s natural to take a deep breath, look around, and… First, there’s the climate to consider.

Dennis Tamura, my friend and neighbor who runs Blue Heron Farm, just down the road, asked me the other day how I was planning and planting for the winter. “We use to wrap most harvesting up by Thanksgiving,” he said, “because after that it was too wet, but now it seems like there’s been a shift and we can keep going all the way through December. But the rains seem to come later now and it’s harder to get an early start in the spring.” I agreed. Yes, it’s only anecdotal evidence, but our climate does seem to be changing in ways that already affect our behavior. I told Dennis I’m still planting some salad and cooking greens in my outdoor ground that I’m planning on picking into the new year, but because I can’t trust the weather to “stay put” I’m also planting in the greenhouse so that, one way or another, I’ve got crops to pick. For each of the last several years we’ve had enough late rain to delay our entry into the outside ground I’ve got here in Corralitos until May. And, just to be really sure we have a harvest we can count on, we’re also planting out in the Hollister-Gilroy area of San Benito County that we know as “The Bolsa” because it’s in a rain shadow of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Even when it’s raining on this side of the hill it’s dusty 30 miles to the east. Right now we’ve got chicories, lettuces, and brassicas, like cauliflower, planted over there.

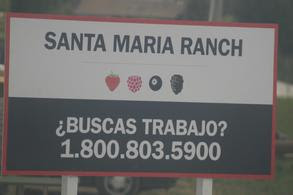

Then there’s the political climate to consider. If the vagaries of the weather weren’t enough, many farmers have to keep an eye on the political climate. Stone fruit growers, for instance, can be dramatically affected by policies out of Washington that would seek to sharply limit or decrease the supply of immigrant, migrant labor. Since native born people seem absolutely unwilling or unable to do this work, there have been in recent years, many examples of fruit crops falling from the trees or rotting on the ground. I’ve noticed that there’s more open ground around Watsonville than I’ve ever seen as berry farms have shut down or moved to Mexico in part because of persistent labor shortages. Grain farmers who count on foreign demand to keep prices up can also suffer when Federal embargoes affect the market. None of this ever affects me directly because we have a diverse planting schedule for fresh produce sold locally but I do need to make sure I have steady work for my crew all year long because the housing situation is so dire that if I lay people off seasonally they’ll have to move to someplace where they can afford the rent and then I’ll struggle to replace them. We work all year long because we have to- not because it’s easy to farm in the winter. We are planning on shutting down for a week or so round Christmas though, just to rest. And later, from the third week of January through the second week of February, we won’t be harvesting, but we will be doing production work in the greenhouses ahead of our early spring harvests.

Then there’s the political climate to consider. If the vagaries of the weather weren’t enough, many farmers have to keep an eye on the political climate. Stone fruit growers, for instance, can be dramatically affected by policies out of Washington that would seek to sharply limit or decrease the supply of immigrant, migrant labor. Since native born people seem absolutely unwilling or unable to do this work, there have been in recent years, many examples of fruit crops falling from the trees or rotting on the ground. I’ve noticed that there’s more open ground around Watsonville than I’ve ever seen as berry farms have shut down or moved to Mexico in part because of persistent labor shortages. Grain farmers who count on foreign demand to keep prices up can also suffer when Federal embargoes affect the market. None of this ever affects me directly because we have a diverse planting schedule for fresh produce sold locally but I do need to make sure I have steady work for my crew all year long because the housing situation is so dire that if I lay people off seasonally they’ll have to move to someplace where they can afford the rent and then I’ll struggle to replace them. We work all year long because we have to- not because it’s easy to farm in the winter. We are planning on shutting down for a week or so round Christmas though, just to rest. And later, from the third week of January through the second week of February, we won’t be harvesting, but we will be doing production work in the greenhouses ahead of our early spring harvests.

And then there’s the economic climate. This year, the Covid 19 plague, wiped out the restaurant market that we’d counted on for a substantial amount of business, and that forced us to make a series of rapid adjustments. Thanks to you and your support, we’ve been able to “weather the storm” so to speak. We’ve kept a crew going, kept planting crops, kept harvesting, and now we’re planning out year 2021 with you and your needs and expectations first and foremost in our mind. Some crops, like our artichoke crop, are already planted, and just waiting for the spring rains to come. For other crops, it’s time to buy seed ahead of the new season. I’ve already got potatoes in the cooler that are destined to be planted out in February- weather permitting. Seed got harder to get this year- and became more expensive- so I’ll be buying my seed earlier than I have in the past. And I’ve been saving seed from my own crops. Carmen will clean some bean seed this afternoon, beating on the pods with a stick and winnowing the crushed hulls away from the seeds, just like people have done for thousands of years. Some things never change.

And then there’s the economic climate. This year, the Covid 19 plague, wiped out the restaurant market that we’d counted on for a substantial amount of business, and that forced us to make a series of rapid adjustments. Thanks to you and your support, we’ve been able to “weather the storm” so to speak. We’ve kept a crew going, kept planting crops, kept harvesting, and now we’re planning out year 2021 with you and your needs and expectations first and foremost in our mind. Some crops, like our artichoke crop, are already planted, and just waiting for the spring rains to come. For other crops, it’s time to buy seed ahead of the new season. I’ve already got potatoes in the cooler that are destined to be planted out in February- weather permitting. Seed got harder to get this year- and became more expensive- so I’ll be buying my seed earlier than I have in the past. And I’ve been saving seed from my own crops. Carmen will clean some bean seed this afternoon, beating on the pods with a stick and winnowing the crushed hulls away from the seeds, just like people have done for thousands of years. Some things never change.

Lastly, I’d like to thank our pick up site hosts. Without the generosity of our site hosts we would not be able to do this business. Shelley who has been our mystery box coordinator for some time now does an amazing job pulling all the pieces together necessary in making this a viable business. She works with the hosts and the customers with untiring customer service. Thanks to all of you we can provide a program that works! On a helpful note, in keeping the pickup site orderly we ask that everyone folds and stacks their boxes prior to leaving the site.

Lastly, I’d like to thank our pick up site hosts. Without the generosity of our site hosts we would not be able to do this business. Shelley who has been our mystery box coordinator for some time now does an amazing job pulling all the pieces together necessary in making this a viable business. She works with the hosts and the customers with untiring customer service. Thanks to all of you we can provide a program that works! On a helpful note, in keeping the pickup site orderly we ask that everyone folds and stacks their boxes prior to leaving the site.

All of us here at Mariquita thank you for your support.

Andy and the crew at Mariquita farm

© 2020 Essay by Andy Griffin. Photos by Andy Griffin.

Yerbas Buenas

Starling is drying bales of Hoja Santa in the food dehydrator so our kitchen is enveloped in an aromatic, herbal haze, prompting me to think about breakfast, lunch, and history. Let’s look at the past before the repast.

History is written by the victors, not the victims, so when I was in kindergarten Columbus “discovered” America. Maybe it’s more accurate to say that history is “rewritten” by the victors. Our past is constantly undergoing reinterpretation as new information comes to light or as we mature enough as a community to look at the old facts in a new way. Also, the oppressed voices of previous generations don’t necessarily remain silenced forever. If a defeated community regains its sense of worth, then it’s natural that the people in it will begin to push back against a dominant culture’s version of history that chooses to ignore their past accomplishments, demean their historic role in creating our present or minimize their right to participate in planning our future. That’s where we’re at today in America, with a fraying establishment’s narrative undergoing some timely and therapeutic re-examination. If your sense of self-worth depends on a historical order that’s under re-evaluation then critical scrutiny by contemporary historians can feel like an attack. A foolish yet natural response of the frightened ignorati is to attack the messenger for bringing the news. So, for example, as the 1619 Project encourages us to reexamine our nation’s history of slavery and racism, it’s getting common to hear slurs being lobbed at the historians who would dare to take another look at our shared past – “communists, anarchists, socialists, liberals, terrorists, snowflakes, etc.” Universities get the brunt of the abuse because they are the vectors of learning and new ideas. But history isn’t just academic; it’s as down and flavorful as the crops in our fields or the food on our plates.

Of course, the myth of Columbus was always an odd half truth. It’s not only that the millions of people already living in the Americas in 1492 didn’t need Columbus to “discover” them in order to exist. Columbus crashed into America. He misunderstood the lands that he encountered upon crossing the Atlantic to BE India. But lots of money was at stake. The lucrative trade in Black pepper, Piper nigrum, that motivated investors to bankroll Columbus’s radical voyage across the Atlantic to India, was too important to ignore. So, to satisfy investors the native Americans became “Indians.” Lacking real black pepper to return home with, Columbus loaded up a cargo of the dried, spicy chilies that the Native Americans were cooking with and called them “peppers.” The American Capsicum species are not related to the Piper nigrum peppercorns of the “Spice Islands” that Columbus thought he’d found his way to, but they are spicy. It’s interesting that once the Spaniards discovered the Pacific and crossed it to Asia the residents of the real Spice Islands were more delighted with the American chili “peppers” than the Europeans who’d “discovered” them were. You don’t want to make blanket declarations about any continent’s culture, but it is true that the chili pepper slipped into Asian cuisines very readily. Today there are many varieties of chili that have been selected and improved by Asian farmers, but they all have their roots in the Pre-Columbian agriculture of the Americas.

Of course, the myth of Columbus was always an odd half truth. It’s not only that the millions of people already living in the Americas in 1492 didn’t need Columbus to “discover” them in order to exist. Columbus crashed into America. He misunderstood the lands that he encountered upon crossing the Atlantic to BE India. But lots of money was at stake. The lucrative trade in Black pepper, Piper nigrum, that motivated investors to bankroll Columbus’s radical voyage across the Atlantic to India, was too important to ignore. So, to satisfy investors the native Americans became “Indians.” Lacking real black pepper to return home with, Columbus loaded up a cargo of the dried, spicy chilies that the Native Americans were cooking with and called them “peppers.” The American Capsicum species are not related to the Piper nigrum peppercorns of the “Spice Islands” that Columbus thought he’d found his way to, but they are spicy. It’s interesting that once the Spaniards discovered the Pacific and crossed it to Asia the residents of the real Spice Islands were more delighted with the American chili “peppers” than the Europeans who’d “discovered” them were. You don’t want to make blanket declarations about any continent’s culture, but it is true that the chili pepper slipped into Asian cuisines very readily. Today there are many varieties of chili that have been selected and improved by Asian farmers, but they all have their roots in the Pre-Columbian agriculture of the Americas.

Corn, squash, beans, potatoes, tomatoes, tobacco, chili peppers, chocolate….; the Native American farmers cultivated so many plants that became major foods for the rest of the world that it’s interesting to look at the varieties that were not immediately adopted by the rest of the world. Ironically, one Native American garden plant that Columbus didn’t “discover” was actually a true pepper variety, related to the Piper nigrum that motivated the Spanish adventure in the Americas in the first place, Piper auritum. The leaves of this plant have a rich, anise-like scent. While the Piper auritum has many names across Latin America- “Anisillo,” “Tlanepa, “Acuyo”- one of the most common names is “Yerba Buena” or “Hoja Santa,” which means “Good Herb” or “Holy Herb.” One problem for food historians is that a wide range of desirable herbs have been called “Yerba Buena.” What’s now the City of San Francisco was once the village of “Yerba Buena,” for example, and the “good herb” in this case was a native California mint family member. If the historical revisionists reject the community’s present name “San Francisco” because it celebrates Catholicism I can see the town’s name reverting to “Good Herb,” but that’s another story.

Corn, squash, beans, potatoes, tomatoes, tobacco, chili peppers, chocolate….; the Native American farmers cultivated so many plants that became major foods for the rest of the world that it’s interesting to look at the varieties that were not immediately adopted by the rest of the world. Ironically, one Native American garden plant that Columbus didn’t “discover” was actually a true pepper variety, related to the Piper nigrum that motivated the Spanish adventure in the Americas in the first place, Piper auritum. The leaves of this plant have a rich, anise-like scent. While the Piper auritum has many names across Latin America- “Anisillo,” “Tlanepa, “Acuyo”- one of the most common names is “Yerba Buena” or “Hoja Santa,” which means “Good Herb” or “Holy Herb.” One problem for food historians is that a wide range of desirable herbs have been called “Yerba Buena.” What’s now the City of San Francisco was once the village of “Yerba Buena,” for example, and the “good herb” in this case was a native California mint family member. If the historical revisionists reject the community’s present name “San Francisco” because it celebrates Catholicism I can see the town’s name reverting to “Good Herb,” but that’s another story.

I started growing Hoja Santa because Matt Gandin, the Chef at Comal in Berkeley, asked me for some. I didn’t know anything about the plant, but Fidel, our farm’s foreman in the greenhouse, was very familiar with the crop so I felt comfortable giving it a try. Our friend and neighbor, Don Pablo, has a nursery, El Capulin, that grows a wide range of ornamental and edible plants that he sells in farmers markets so he set us up with some plants and we were off and running. The Hoja Santa plants grow big and tall. They require some protection from the cold of winter but they’re pretty hardy. Fidel tells me that “every family” in Oaxaca has an Hoja Santa plant growing in their yard, so it’s not worth a farmer’s time to produce the crop for sale, but the leaves are used in daily cooking. The big, heart-shaped, aromatic leaves are used to wrap fresh cheeses and they lend their scent to the food. Sometimes the fresh leaves are used as wrappers for other foods too, the way that corn husks are used to wrap tamales. And the leaves are dried and crumbled too, for use in egg and bean dishes, in soups and in stews. Because the Hoja Santa has a sweetness to it there are also a number of drinks or cocktails that can be made using it’s flavoring. In my own kitchen I’ve used Hoja Santa to flavor scrambled eggs and quesadillas. When it’s not so hot outside and my mood turns more to soup I’ll try it in broths. This Friday I’m thinking I’ll try some Holy Leaf cocktails!

I started growing Hoja Santa because Matt Gandin, the Chef at Comal in Berkeley, asked me for some. I didn’t know anything about the plant, but Fidel, our farm’s foreman in the greenhouse, was very familiar with the crop so I felt comfortable giving it a try. Our friend and neighbor, Don Pablo, has a nursery, El Capulin, that grows a wide range of ornamental and edible plants that he sells in farmers markets so he set us up with some plants and we were off and running. The Hoja Santa plants grow big and tall. They require some protection from the cold of winter but they’re pretty hardy. Fidel tells me that “every family” in Oaxaca has an Hoja Santa plant growing in their yard, so it’s not worth a farmer’s time to produce the crop for sale, but the leaves are used in daily cooking. The big, heart-shaped, aromatic leaves are used to wrap fresh cheeses and they lend their scent to the food. Sometimes the fresh leaves are used as wrappers for other foods too, the way that corn husks are used to wrap tamales. And the leaves are dried and crumbled too, for use in egg and bean dishes, in soups and in stews. Because the Hoja Santa has a sweetness to it there are also a number of drinks or cocktails that can be made using it’s flavoring. In my own kitchen I’ve used Hoja Santa to flavor scrambled eggs and quesadillas. When it’s not so hot outside and my mood turns more to soup I’ll try it in broths. This Friday I’m thinking I’ll try some Holy Leaf cocktails!

The Hoja Santa plants stop growing and lose most of their leaves here during the cold weather or winter, so we’re drying what we can now while the plants are green and fluffy. We will be preserving other herbs too, as time allows. In the greenhouse we’re propagating more lemon verbena, oregano, marjoram, savory, thyme, rosemary, sage, nepitella, lavender and mints. We’ve been growing a lot of roses in the yard too- we’re up to over a hundred plants- with an eye to rose bouquets, rose petals, and rose hips. They’ve all got their uses in the kitchen and they’re all Yerbas Buenas.

© 2020 Essay by Andy Griffin. Photos by Andy Griffin and Starling Linden

Smoke in the air. Fire in the belly.

Covid creeps closer; a worker on our landlord’s farm fell ill and is in quarantine at present. I’m not too alarmed (yet) for our farm because we don’t share a workspace with that farm crew, we keep our distance, we have prophylactic measures in place, and the sick worker is being cared for. But I am angry. At a time when the country is threatened by this illness and so many people are out of work and struggling to pay their bills, it’s insane that the president ignores the advice of his own administration’s medical experts and holds mass indoor rallies to celebrate his vanity and trumpet his ignorance. What can you say about his so-called “conservative” supporters who seemingly seek to conserve nothing more than their own sense of privilege? Meanwhile, the essential workers, like the farm workers, must labor to survive in an increasingly dangerous environment. I’m mindful that no matter how careful we are at work, at the end of the day the workers must return home to crowded apartments where social distancing is impossible. For many farm workers the workplace may be their safest place. It’s hard to keep positive sometimes and I’m counting the days until I can vote for change. Meanwhile, we’re already planting the crops that we’ll be harvesting in what I hope will be a new era where medical science gets renewed respect.

The smoke has been hard to live with too. It’s been difficult to breathe at times, and every breath is a reminder of what we’re losing to the fires. As a farmer, it’s easy to observe how the smoke is slowing the growth of some crops. A friend with a fruit farm remarked this morning how her fig crop is ripening more slowly under these unseasonably dark skies. In our own greenhouse we can see how the arugula is responding to the lower light by growing slower and more etiolated. Climate change deniers, like Trump and the chumps who crowd his rallies, reject the idea that human activity is capable of changing the climate. But the smoke tells the truth. Poor management is the issue, says the man who bankrupted a casino, as well a number of other businesses, and he blames Democrat States for not “sweeping the leaves.” Of course, many of the fires are on Federal land- supposedly his jurisdiction and responsibility- so he’s an idiot who only speaks to “own the libs” and blame the victims. But even a broken clock is right twice a day; it’s true that poor forest management is partly to blame for these catastrophic fires, which only proves the point that human behavior DOES have a lot of influence on the climate. So, while we wait for an opportunity to depose the Twitler, we strap on our masks against the Covid virus and the smoke and we do the essential work of harvesting food. Right now we’re in the middle of tomato season, while much of the crop has been lost to scalding heat and disrupted markets, there’s still plenty to pick over the next month.

So things are sad, but one remedy for depression is to stay busy. We don’t have the luxury of hiding from the smoke but at least it smells great inside our house. The crew has been grooming the beds of perennial herbs, and Starling has been running the dehydrators 24/7, drying oregano, thyme, and marjoram. These aromatic, mint family herbs all go with tomatoes like cookies go with milk, so it makes sense to pick them now that it’s time to make tomato sauce for the winter. With so much uncertainty over the viability of supply chains we’ve noticed more interest on the part of the public to lay aside a stash of tomato sauce against the coming winter. Or maybe it’s just that being out of work means more people have time to make sauce. Anyway, our house smells like herbs and it’s great. And it’s good for the oregano, thyme, and marjoram plants to get a trim too; that way the plants don’t go to flower, but are stimulated to produce fresh growth. Oregano, thyme, and marjoram are perennial in this climate and will grow all year if encouraged. I want to have healthy plants come winter because these herbs also marry well with the soups, stews, and roasted winter veggies. Speaking of winter, we picked the first “winter squash” this week and you have them in the box. These are “small” Napolitano squash- and they are small, considering that the “big” ones reach 30 and 40 pound apiece. I’m still thinking about how we’ll move the whoppers. Cook Napolitano squash like their Butternut cousins. They’ll keep for up to year too, if you can’t use them now. That’s a fact, not Trumpstyle b.s. – keep the squash out of direct sunlight in a cool, dry space and they’ll only get sweeter with time.

So things are sad, but one remedy for depression is to stay busy. We don’t have the luxury of hiding from the smoke but at least it smells great inside our house. The crew has been grooming the beds of perennial herbs, and Starling has been running the dehydrators 24/7, drying oregano, thyme, and marjoram. These aromatic, mint family herbs all go with tomatoes like cookies go with milk, so it makes sense to pick them now that it’s time to make tomato sauce for the winter. With so much uncertainty over the viability of supply chains we’ve noticed more interest on the part of the public to lay aside a stash of tomato sauce against the coming winter. Or maybe it’s just that being out of work means more people have time to make sauce. Anyway, our house smells like herbs and it’s great. And it’s good for the oregano, thyme, and marjoram plants to get a trim too; that way the plants don’t go to flower, but are stimulated to produce fresh growth. Oregano, thyme, and marjoram are perennial in this climate and will grow all year if encouraged. I want to have healthy plants come winter because these herbs also marry well with the soups, stews, and roasted winter veggies. Speaking of winter, we picked the first “winter squash” this week and you have them in the box. These are “small” Napolitano squash- and they are small, considering that the “big” ones reach 30 and 40 pound apiece. I’m still thinking about how we’ll move the whoppers. Cook Napolitano squash like their Butternut cousins. They’ll keep for up to year too, if you can’t use them now. That’s a fact, not Trumpstyle b.s. – keep the squash out of direct sunlight in a cool, dry space and they’ll only get sweeter with time.

Starling is also drying herbs for teas and herbal infusions. Yes, it’s an Allman Brothers’ tune, but “Sweet Melissa” is one name for Lemon Balm or Melissa officinalis, which makes a delightful tisane. It’s a mint family member too, and “Lemon mint” is another name for it. I propagated the plants we’re picking now from wild plants I found in the redwood forests 20 years ago. With so many local redwood forests burned I comfort myself to know that the redwoods will largely survive the fires and grow back. Sweet Melissa will survive too- she’s tougher than she looks. We might talk about about “destroying the planet,” but the planet is going to be fine. The cockroaches, the rats, the ground squirrels, and the flies are going to be fine- it’s our grandchildren who are going to suffer if we don’t take responsibility for our actions on the planet. A true conservative with family values would value the future; these Trump republicans are like locusts without the grasshopper’s ability to fly without burning oil.

Then there’s apple mint, another survivor. It makes a pleasing herbal tea and nothing can kill this plant! It does have a sweet apple scent, and it’s calming, which is always a good trait. I should drink some now!

Then there’s apple mint, another survivor. It makes a pleasing herbal tea and nothing can kill this plant! It does have a sweet apple scent, and it’s calming, which is always a good trait. I should drink some now!

And finally there’s Lemon verbena, which is not a mint family member. It makes a delightful tea with a flavor that is just the right thing to help ease us into fall. Various claims are made about the health benefits of Lemon Verbena. All I can say is that it has to be better for you than injecting bleach.

We will be rolling out lots more dried herbs as the weeks unfold; summer savory, sage, sweet laurel, rosemary, lavender and a special herb that I will talk about later, Hoja Santa. November can’t come quick enough and when it does we can all raise our cups with hope for what the future can bring. Let’s look forward to fall cooking and a celebration that will have us all toasting to the opportunity of breathing new life into our land.

© 2020 Essay by Andy Griffin. Photos by Andy Griffin and Starling Linden

Gems, Jewels and Beans…

Last winter, right before Covid erupted into our midst, I had the opportunity to visit the Tucson Gem and Mineral show in Arizona. Sure, I’d been told just how big the event was, how every year the whole city of Tucson surrenders itself to an ultimate “rock show.” But I wasn’t prepared for the scale of the event; block after block of tents, and hotel rooms and pavilions and parking lots and convention center halls and county fairgrounds crammed with vendors offering every kind of crystal and gem and mineral for sale by the piece, the kilogram, the pallet, or the ton. There were hollow amethysts geodes big enough to park a motorcycle in and tiny opals that flash with kaleidoscopic displays of light and color. Every kind of green and blue could be found hiding in heaps of jade and turquoise alongside other stones that seemed like fossilized rainbows. The variety of beautiful rocks coming out of the ground was overwhelming and it seems marvelous that the dark, sunless earth beneath our feet can be capable of producing such a majestic display of color. Of course, what’s true for jewels is true for beans too!

One year I tilled up the level acre of ground I have in my front yard and planted a row of every kind of bean I could find seed for. I had over 30 varieties planted when I was done, not including fava beans or garbanzo beans, as they are not true beans. Yes, favas and garbanzos are legumes but they are more closely related to vetches than to kidney beans. True beans are classified as Phaseolus varieties and they evolved in the “New World,” having been selected from their wild cousins and cultivated and tamed by Pre-Columbian indigenous farmers across the middle Americas. I planted red beans, black beans, striped beans, dotted beans, green beans, yellow beans, pink beans, white beans splashed with color….an overflowing treasure chest of lustrous little jewels that had been saved by different farmers over the centuries, planted side by side so that I could judge them on their merits. My experiment proved one thing to me- there is an obvious reason why the common Pinto bean is SO common in the supermarket!

We humans make a fetish out of rarity; black carbon that has been compressed into a briquette form is valued (a little) for its use as a barbecue fuel. Take that same carbon and compress it deep in the earth under millions of tons of rock for millions of years and you’ll get a diamond- rarer and more expensive. The Pinto bean is like a charcoal briquette- valued, for sure, and useful, but not precious enough to put on a wedding ring. Planted next to so many of its colorful, mottled, striped, speckled, spotted leguminous cousins, and given the same regimen of sun, soil, water, the Pinto bean grossly out-produced all of its colorful rivals. My fresh Pinto beans tasted great too, and like all really fresh beans, they didn’t take long to cook up tender and savory with no ” overnight pre-soaking” ritual necessary. The efficiency, economy, and practicality of this bean is astonishing. So, this year I didn’t grow Pinto beans for you. Instead, I chose to plant Tongue of Fire beans because they’re beautiful- a bit rarer to find in the marketplace maybe, and not necessarily tastier than their common cousins, but gorgeous.

We humans make a fetish out of rarity; black carbon that has been compressed into a briquette form is valued (a little) for its use as a barbecue fuel. Take that same carbon and compress it deep in the earth under millions of tons of rock for millions of years and you’ll get a diamond- rarer and more expensive. The Pinto bean is like a charcoal briquette- valued, for sure, and useful, but not precious enough to put on a wedding ring. Planted next to so many of its colorful, mottled, striped, speckled, spotted leguminous cousins, and given the same regimen of sun, soil, water, the Pinto bean grossly out-produced all of its colorful rivals. My fresh Pinto beans tasted great too, and like all really fresh beans, they didn’t take long to cook up tender and savory with no ” overnight pre-soaking” ritual necessary. The efficiency, economy, and practicality of this bean is astonishing. So, this year I didn’t grow Pinto beans for you. Instead, I chose to plant Tongue of Fire beans because they’re beautiful- a bit rarer to find in the marketplace maybe, and not necessarily tastier than their common cousins, but gorgeous.

We’re going to pull up every mature bean plant this week and strip off every bean. Fall is approaching and we’re scampering to open up as much ground as we can so we can begin planting for winter harvests. Some of the beans that we pick will be rattling around inside completely dried pods. These beans may look “dried” but they have a great deal of residual moisture in them and they will cook very promptly compared to some store bought dried beans. I’ve been scandalized at different moments in my life when the dried beans I’d gotten in the store took hours to cook- they must have been SO old! Once you’ve shelled your beans (a good chore for any kids lurking about) then give them a quick look through to take out any damaged or withered beans before putting them in a pot of water and bringing them to a simmer. Check the beans every so often – they won’t take long to cook. True, as the beans cook they will lose the cute red markings that made them so attractive raw, but they’re going to taste great. Or maybe you don’t cook these beans at all. If you were to store these beans in a cool, dry place, they’d make perfect seed stock for your own backyard bean garden next spring. This is one reason why beans are even more valuable than mineral jewels; you can’t plant a sapphire back in the earth and return in four months to harvest a bucket of gems.

We’re going to pull up every mature bean plant this week and strip off every bean. Fall is approaching and we’re scampering to open up as much ground as we can so we can begin planting for winter harvests. Some of the beans that we pick will be rattling around inside completely dried pods. These beans may look “dried” but they have a great deal of residual moisture in them and they will cook very promptly compared to some store bought dried beans. I’ve been scandalized at different moments in my life when the dried beans I’d gotten in the store took hours to cook- they must have been SO old! Once you’ve shelled your beans (a good chore for any kids lurking about) then give them a quick look through to take out any damaged or withered beans before putting them in a pot of water and bringing them to a simmer. Check the beans every so often – they won’t take long to cook. True, as the beans cook they will lose the cute red markings that made them so attractive raw, but they’re going to taste great. Or maybe you don’t cook these beans at all. If you were to store these beans in a cool, dry place, they’d make perfect seed stock for your own backyard bean garden next spring. This is one reason why beans are even more valuable than mineral jewels; you can’t plant a sapphire back in the earth and return in four months to harvest a bucket of gems.

A lot of the beans we pick today and tomorrow will be harvested at the fresh “shelly-bean” stage. These bean pods are fully filled out with plump beans but have not dried out. These beans will even take less time to cook than their recently dried friends. The pods are a bit more difficult to open than the dried pods but it’s no big struggle and they’re a very pretty red color. This bright pod might seem like a very frivolous fashion-forward statement coming from a humble bean plant, but it’s actually a very practical aspect of the Tongue of Fire bean. Most Tongue of Fire beans are harvested at this full-pod but tender stage, the beans being plucked from among green leaves, and the bright red of the pod makes the beans very easy for the picker to see as they hang in the foliage. If you get beans that have been harvested at this young stage you should store them in the refrigerator until use so that they don’t wilt. These fresh beans would be great in soups and bean salads, which brings a last comparison between beans and jewels to mind; Marilyn Monroe sang “Diamonds are a girl’s best friend,” and I’m not going to argue with her, but you can’t eat jewels.

A lot of the beans we pick today and tomorrow will be harvested at the fresh “shelly-bean” stage. These bean pods are fully filled out with plump beans but have not dried out. These beans will even take less time to cook than their recently dried friends. The pods are a bit more difficult to open than the dried pods but it’s no big struggle and they’re a very pretty red color. This bright pod might seem like a very frivolous fashion-forward statement coming from a humble bean plant, but it’s actually a very practical aspect of the Tongue of Fire bean. Most Tongue of Fire beans are harvested at this full-pod but tender stage, the beans being plucked from among green leaves, and the bright red of the pod makes the beans very easy for the picker to see as they hang in the foliage. If you get beans that have been harvested at this young stage you should store them in the refrigerator until use so that they don’t wilt. These fresh beans would be great in soups and bean salads, which brings a last comparison between beans and jewels to mind; Marilyn Monroe sang “Diamonds are a girl’s best friend,” and I’m not going to argue with her, but you can’t eat jewels.

© 2020 Essay and photos by Andy Griffin.

Potatoes and the web

The potatoes in this week’s share box are “new” potatoes; that is, they have been dug from beneath green plants that are only just beginning to wilt down. As such, these very fresh potatoes will not store for a long time the way that a cured potato can. But do they ever taste good! They should be kept in the refrigerator until you use them so that they do not wilt. Be aware, too, that they will cook much faster than a “regular” potato, so adjust your preparation times accordingly. I have a few more things to say about potatoes today but I have been encouraged by Shelley and my partner, Starr, to say a few words about technology.

No, I don’t know much about technology, and I don’t have much that is meaningful to say, but…..

This has been a very challenging year for our business and 2020 promises to continue to be weird and unpredictable all the way up until the ball drops on TV at 11:59 PM Eastern Standard TIme on December 31st. We’ve been muddling through, but even the potatoes in this week’s box speak to the difficulties we’ve been working through. When the Covid crisis announced itself to American civic life in early March one of the first consequences was financial chaos. For a while we had no monies on hand to buy seeds the way we usually would, and I was unable to source the certified disease-free seed potatoes the way we usually do.

We’re getting to the “technology” but….

Potatoes are underground stems, not roots, and potato plants are not typically started from seeds, but from pieces of potatoes that have viable “eyes” or buds that will develop new plants. Since potatoes can pick up viruses from the soil that affect production it’s a good idea to source the potatoes that will be cut into sections for planting from companies that specialize in disease free planting stock. Insects are a common vector for potato viruses so these farms are usually located in places like Oregon or Idaho where freezing wintertime temperatures keep insect pressure to a minimum. Good certified disease free potato ground is also often highly mineral- perhaps volcanic in origin- because these soils are less hospitable for the viral pathogens that affect potatoes.

“Viruses” affect computer systems too….

Anyway, I couldn’t source the disease free seed potatoes that I wanted when I wanted them. I decided to use the last few cull potatoes we had on hand – the little weird ones that were too ugly to sell, the ones that had been damaged by the shovel or had a sun scald burn on one side, or where a beetle had chewed a hole in the side. So we couldn’t hope for a big crop, but I figured we’d get by. However, the website we had been using to support our business was very out of date and after turning the issue over in our minds we decided we couldn’t get by with it indefinitely. With all the unquantifiable variables and insecurities and opportunities alive in the business and growing environment we had to make a decision to go forward and invest in new platforms that would help us keep growing and selling and delivering- or quit. So we decided to go for it, and we’re now rolling out the new website and e-commerce platform this week. We’re hoping we’ll be better able to handle transactions in a transparent and more reliable fashion than before. The labor of entering all the info that our old system required was unsustainable. We strive to be a model of “sustainable” agriculture, but if we can’t sustain ourselves we can’t care for the soil.

The reflection I went through when deciding to go ahead with getting a new website reminded me that sometimes I get sick of farming and quit. The last time I quit was in the winter of 1990 after a severe cold front in December ’89 destroyed all of the crops we’d planted to survive on during the winter. I took a trip to Bolivia to look at the cactus forests in the red-rock desert country of the Tarija Department, down near the frontera with Argentina. I found myself staying in the little mountain town of Tupiza and venturing out into the deserts to look for cacti. One afternoon, after a long hike and after having been rained on and then baked by the sun I was dragging my tail feathers into town, sore-footed, and still a few blocks from the little room I was staying in when I heard children laughing at me.

I turned and saw three girls, about 13 years old, dressed in the uniforms of the Catholic school they attended. They squealed and ran down a side alley. Since I’m so tall and white and looked so strangely out of place I was used to people staring and commenting. I kept plodding along. Then the girls suddenly popped out onto the sidewalk in front of me, and the boldest girl made to block my path.

“Are you German?” she demanded to know.

“Good afternoon, Senoritas,” I responded. “No, I’m not German. I’m a Californian.”

The girls went into a huddle without getting out of my way. The bold one again addressed me, a bit more diplomatically.

“We have to do a report for civics on foreigners, and we were going to do it on Germans, but since you’re here we will interview you instead.”

“What would you like to know?” I asked.

“You can make yourself presentable and come to my house at 5pm,” she said, “and we will interview you.” She gave me her address, and with that the girls raced off.

I cleaned up, then showed up. I knocked on the door of a little cinder-block house, quite respectable but humble in it’s out door appearance, and was seated in the living room. There was a figurine of the Virgin on a shelf, a portrait of the Pope on the wall and a crucifix, and a small TV on a bureau. Against one wall was a couch where two of the girls were seated, and there was an armchair with the third. And in the middle of the room, dominating the room the way Mt Shasta dominates northern California, or Fuji dominates Japan, was an immense multicolored pile of potatoes. I was served tea and cookies, and the girls got right down to business.

“Are you married?” “Where’s your wife?” “How old are you?” “How much money do you make?” “Are you Catholic?” “Do you have any children?”

“Senoritas,” I pleaded. “One at a time. No, I’m not married?”

“Why not?”

“I have not yet found the right woman.”

“But you’re looking, right? How old are you?”

“I am 30. When I find the right woman, and I’m making a reasonable income and have some degree of security in my life, then maybe I can start a family.”

“What do you do for a living?”

“I’m a farmer.”

“?????!!!!!!”

The girls could handle the fact that I was unmarried, 30, and not Catholic. They could believe that I’d travel halfway around the world to look at cacti, and they were even willing to accept that I was not German. But they did not buy the idea that I was a farmer. Their fathers were farmers. Their fathers got up every morning before dawn as their fathers had done before them, and they went to their little plots of ground where they grew potatoes. They didn’t travel. They grew many varieties of potato as insurance because some years one kind would do better, and other years favored a different kind. And when the harvests came in they dug the potatoes by hand and stored them in the house so that their crop would be safe for thieves and rodents and insects and cold temperatures. With their year’s food supply assured, they’d sell their excess harvest in the Tupiza farmers market. Farmers don’t travel.

“But I am a farmer,” I said. And I told them about the crops I cultivate them and how and where I sell them. The girls weren’t going to tell me I was lying, but they weren’t convinced. After another huddle they arrived at a solution. “You are an ingeniero agronomo,” they declared. “That’s why you know about growing but get to travel and are not rooted to the soil like a potato.”

With the issue of my suspicious livelihood out of the way they were able to get back on track for an in-depth exploration of my religion, or lack there-of, my family, or lack there-of, and my income, or lack thereof. When they were finished taking notes I was on my way. They were lovely girls; charming, direct, funny, and sincere, and my encounter with them was one of the more enjoyable visits I’ve ever had with anybody. Today I wonder what they’re up to now and I ask myself how far technology has made itself at home in Tupiza. There was that TV in the living room, after all, so maybe the three girls grew up to manage their family farms’ on-line sales platforms. Who knows; maybe one of the three grew up to be a high-tech sorceress here in Silicon Babylon? We’re nothing, if not a diverse society of doers and makers, and technology is just as important down in the earth of the potato patch as it is atop the highest skyscraper where the tech wizards eat the potatoes we grow. We look forward to your feed-back as we go about our business of trying to feed you.

© 2020 Essay and photo by Andy Griffin.